Holmes Report 09 Jan 2017 // 8:40AM GMT

1. Air China's race row

It's difficult to know exactly what Air China's editorial team was thinking when it published an article in its inflight magazine that warned passengers about visiting certain areas of London. "Precautions are needed when entering areas mainly populated by Indians, Pakistanis and black people," proclaimed the Wings of China magazine, prompting derision and outcry among London MPs and residents.

It took Air China a couple of days to apologise after social media quickly turned the offensive comment into a global news story. This, says Sermelo founder Jonathan Jordan, was far too slow.

"Although a letter of apology was issued sometime later by the airline and the offending magazine – Wings of China – was withdrawn from circulation, the bird had flown and a deluge of angry comments dominated social and mainstream media," said Jordan.

"In our connected world, a crisis plan needs to provide an initial response within 15 minutes, or you risk the consequences, the criticism and the anger."

The wider implications of the crisis, adds Weber Shandwick China CEO Darren Burns, should not be missed either — reflecting the cultural challenges facing Chinese companies as they expand globally.

"I think the reality is we are seeing more Chinese companies put their foot in it as they expand globally," says Burns. "I’d argue this happens when nations emerge – the Japanese in the 1970s and 1980s, the US in the 50s – even earlier.

"Gaffes for Chinese companies are bound to happen as they expand rapidly and adapt to being relevant and culturally sensitive to their audiences around the world," continues Burns. "Similarly many successful MNCs in China have adapted and learned over the last 30 years and those that do well know how to connect their brand DNA to a local audience. That’s a science and an art. This ship is just underway for China." — AS

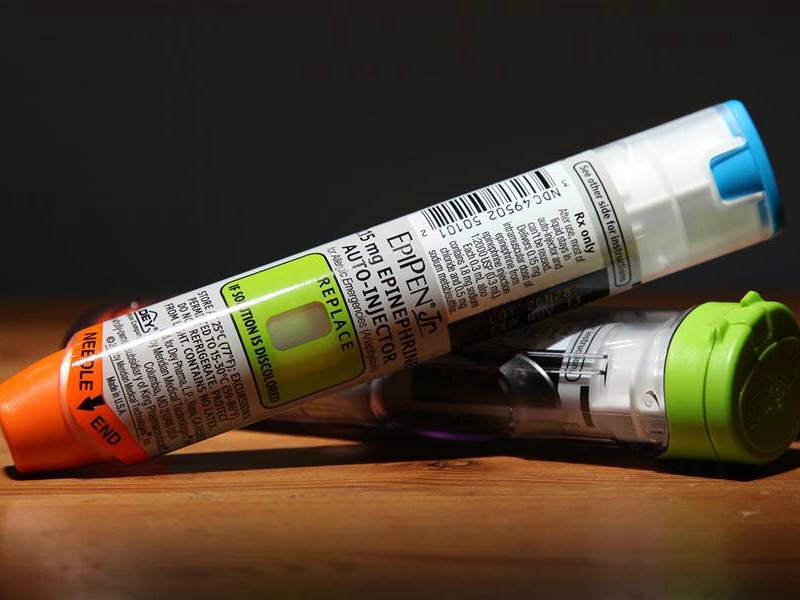

2. Mylan raises EpiPen prices

It’s hard to imagine a more disturbing lead-in than the one that opened an NBC report on Mylan’s life-saving anti-allergy device EpiPen. "The cost of saving your child's life has gotten a lot more expensive." As if that wasn’t bad enough, the story was promptly tweeted out by then-presidential candidate Bernie Sanders as part of his campaign to rein in drug prices.

As William Comcowich, chief executive of CyberAlert, pointed out in a column, an online petition gathered more than 80,000 signatures in 45 days and prompted more than 120,000 letters to Congress.

The New York Times and Hillary Clinton soon piled on, the company’s stock price tumbled, and CEO Heather Bresch badly botched a CNBC interview.

"Of all the corporate crises in 2016, Mylan’s epic disaster with the EpiPen stands out as the one that generated the most anger," says Michael Robinson, a veteran corporate affairs counselor who recently launched his own firm, The Montgomery Strategy Group. "Not a surprise given that consumer-facing companies are uniquely in possession of their customers’ trust.

"With the EpiPen literally the difference between life and death for millions (including children) and the fact that Mylan has no viable competition for the product, the made-for-cable-news tale of putting profits over people was complete. Yes, list pricing of pharmaceuticals is complicated and so is insurance reimbursement, but that is precisely the job of corporate communicators, to make an organization’s narrative clear and concise. And ideally to do so ahead of time, especially in an industry that is under the microscope and not known for its transparency.

"By the time Mylan CEO Heather Bresch testified before Congress, she embodied the classic crisis conundrum ‘when you’re explaining your losing,’ with predictable results."

Gil Bashe, who leads the healthcare practice at New York’s Finn Partners, points to the broader implications for the healthcare sector: "The Mylan EpiPen crisis is a self-created reputation fiasco, another fallen pharma domino—along with KV Pharma, Turing and Valeant. Mylan joined a small, highly visible list of industry outliers who betrayed public trust and the core public belief that pharma companies aim to help patients live longer, healthier lives.

"The big takeaway for communicators and C-Suite leaders—whether championing generics or brands—is to always remember that their companies coexist within the healthcare ecosystem. Whenever their decisions impact patients, payers, physicians and policymakers negatively, these voices will respond publicly and punitively."

As EpiPen became a rallying moment for responsible pharma industry executives, Allergan CEO Brent Saunders stepped forward with a "social contract" that outlined the company’s principles around price transparency and acknowledge the importance of sector-wide collaboration. Says Bashe: "More and more health communication leaders would be wise to reaffirm the great mission—to help heal and sustain life—committing to greater effort to place patients at the center." — PH

3. Tesco's accounting scandal

Tesco is no stranger to our annual crisis review, with it's 2016 entry actually sparked by a debilitating accounting scandal that was first discovered in 2014. Alongside food safety scares and continued financial underperformance, it is little surprise that the giant retailer has become something of a byword for corporate misbehaviour, reflected in considerable executive turnover at the top of the company, including the arrival of new corporate affairs head Jane Lawrie towards the end of 2016.

In 2016, the company faced legal action by a group of investors who claimed to have lost £150m due to the supermarket's 2014 accounting irregularities scandal. As Lansons CEO Tony Langham points out, Tesco's experiences illustrate how "problems from high level corporate misbehaviour have a long tail", with the fallout often continuing for years.

"In 2016 the SFO charged three former Tesco executives over the accounting scandal and the trio are expected to appear in court in May this year for a plea hearing before being tried in September," explains Langham. "The shareholder action will also rumble on and there is still an FCA investigation to conclude, before presumably, action from other bodies including the FRC."

Tesco's travails, adds Lansons, also demonstrate how businesses cannot talk their way out of corporate transgressions at the highest levels of a company. "Reputation is the product of the behaviour of everyone in an organisation and any short term gain from misbehaviour (in this case maintaining the share price) is rarely worth the long term pain," he explains.

"Some of Tesco’s senior team didn’t "live the brand" – and its governance structures took too long to discover the problems. We can only hope that these cultural problems have been fixed, but only time will tell."

Tesco has fought back from its problems by initiating a price war with discount retailers, shoring up its share price but doing little else to convince the public that its motivations are sinless. In September 2016, the Institute of Directors ranked Tesco the lowest of all FTSE-100 companies for corporate governance. "This leaves the business not only with a drag on its share price, but also a handicap in influencing Government and other key stakeholders," says Langham.

Indeed, Langham believes a "bolder route" may well be required if Tesco is to shake off a lingering reputation for malfeasance. "Tesco could publicly move to tackle Theresa May’s inequality and governance agenda by showing leadership on issues ranging from worker representation on boards, to employment of school leavers to broader ESG (environmental, social, governance) reporting to levels higher than required by the regulators," he suggests.

Without such moves, Langham sees little that will move Tesco's reputation needle upwards in 2017, even factoring in the new management at the company. When Dave Lewis became CEO of Tesco in 2014, he spoke publicly of "the need to begin the long journey back to building trust and transparency into our business and brand."

That journey appears to be taking longer than expected. "The fact it is under new management is of course a positive factor but to rebuild trust, Tesco will need to demonstrate the best of behaviours throughout its operations and be ready to react quickly to each and every twist and turn," concludes Sermelo's Jonathan Jordan. "Tesco’s new leader certainly seems up to this task, but the events of 2017 will certainly keep him and his team on their toes." — AS

4. Data breach at Yahoo!

Data breaches have become almost commonplace—last year’s crisis review covered breaches at Ashley Madison, Experian, Hilton, Hyatt and more—the December announcement from Yahoo! stood out for a couple of reasons: first, it involved more than a billion user accounts and second it involved cyber-attacks that dated back to 2013.

And, as Edelman chair of crisis and risk Harlan Loeb points out, it represented the first-time reputational damage from a hacking crisis presented a material valuation event: Verizon put its plans to acquire Yahoo on hold.

Loeb points to several key learnings from the incident, including the fact that data breaches can go undetected for a long time. "Although most incidents take 146 days to be detected, companies have great difficulty explaining why it takes so long," he says. "And it is not satisfying to customers to acknowledge that the ‘offensive’ bad guys have the edge over the ‘defensive’ good guys. Often, therefore, the best strategy lies in addressing questions on timing using the date range of attacks and focusing proactive messaging on steps taken since the incident was detected."

In addition, companies have to assess which information needs to be shared with specific stakeholders. Says Loeb: "This is especially true for an organization such as Verizon, which has an entire division dedicated to helping companies respond to security incidents."

And finally, companies need to understand that security incidents can cascade. Yahoo—like Target before it—was forced to disclose a second security incident quickly after the first became public. Loeb’s advice: "Wait until a forensics investigation is complete or nearly complete before disclosing an incident. While a company’s hand may be forced to disclose an issue mid-investigation, it’s typically best to possess more certain information before communicating to ensure that the company is ‘telling all.’ Though a company may get dinged in the short term for waiting to disclose, the potential reputational damage triggered by disclosing incomplete information and multiple incidents is a ‘death of a thousand cuts.’"

And finally, the Yahoo incident may have wider implications. According to Michael Robinson: "The ultimate legacy of the mammoth Yahoo breach may well be the establishment of a de facto national data breach disclosure standard by the Securities & Exchange Commission given the clear and obvious material impact of this breach on the company’s investors and its position in the marketplace. Communicators can seize the opportunity to work even closer with their legal and investor relations colleagues to develop the internal consensus needed to drive the right type of proactive disclosure." — PH

.jpg)