Arun Sudhaman 01 Dec 2013 // 5:00PM GMT

Independent, family-owned and scrappy to a fault, Edelman’s turbo-charged growth over the past decade has owed much to its status as a challenger brand. It has moved swiftly to capitalise on gaps in the market, investing ahead of its rivals and scooping Global Agency of the Year honours twice in the past three years from the Holmes Report, as well as Agency of the Decade in 2010.

As all market leaders know, though, the challenger mentality becomes a little more difficult to maintain once you secure the number one spot, which Edelman did three years ago. It is a position that brings a different set of demands, often serving to stymie the very innovation that served a company so well on its ascent to the summit.

For Edelman, that probably means preserving the firm’s unique — some might even say paranoid — culture. “That constant paranoia is eminently healthy,” says one senior executive at the agency. “It permeates the firm — everybody is looking for something new.”

Which might also explain why, earlier this year, Richard Edelman gathered his top global leaders in Hamburg. There, he unveiled a new plan designed to keep Edelman ahead of its competitors, focusing on five key themes for growth.

For a company that has made much of its ‘outsider’ status, Edelman’s lofty perch as the world’s largest PR firm sees it strike a different pose, particularly in the eyes of newer agencies, hybrid beasts that are growing up amid an unparalleled technological shift away from the traditional public relations model.

Even as the financial gap between Edelman and its major network rivals has increased, moreover, the difference in mindset has shrunk. This may be because many of the agency’s rivals have wised up to some of the things that have set Edelman part — such as a strong digital practice and a robust global client management engine.

But it is also because Edelman cannot really be classed as those interlopers from Chicago any longer. Richard Edelman is as fluent in management-speak as anyone in the corporate world, as likely to be seen in Davos as he is in Dalian or DC. And even if Edelman’s independence grants it an enviable measure of financial latitude when compared to its publicly-held peers, it remains hamstrung by an unwillingness to make major acquisitions, putting it at a potential disadvantage if clients continue to seek holding group solutions to their marketing communications needs.

More on which later. Any analysis of Edelman’s breathtaking performance over the past decade, during which it tripled in size, must begin by acknowledging that the firm does not appear overly afflicted by self-doubt. Growth continues to impress, forecast to reach 12.5% in 2013. Which means that Edelman, at around $750m in revenues, is not only bigger than its key rivals, but is also getting bigger than most of them at a faster rate.

Eye-catching numbers like those suggest that the risk of complacency is being taken seriously. While global meetings such as Edelman's Hamburg event are hardly the stuff of which legend is made, agency veterans like to point out that a similar confab in Los Angeles, in 2003, effectively served as the launchpad for the firm’s dizzying rise over the next 10 years.

The hope, as Richard Edelman himself notes, is that Hamburg will have a similar effect on the agency. Perhaps the clearest evidence that this was not an extended gabfest came soon after, when Edelman peremptorily announced the end of any aspiration towards building a holding group. From now on, he said, the firm would focus more closely on its public relations capabilities, along with digital and research, rather than attempting to acquire advertising and media agencies.

Earlier this month, meanwhile, the Holmes Report revealed that the agency is evaluating a radical restructuring of its account teams, after smaller rival GolinHarris initiated a similar process two years ago. In addition, the firm has hired Glenn Engler as global chief of staff and corporate strategy head, to help Richard Edelman implement the Hamburg plan.

These moves, which will also include a new brand positioning campaign in early 2014, have surprised many in the industry, but probably shouldn’t. While the past couple of years have not always indicated a clear overarching strategy behind some of Edelman’s global moves, a senior executive at the firm dismisses the notion of strategic drift, noting that the agency is as restless as it ever was.

Driven by Richard Edelman’s own mercurial nature, even Edelman veterans find the tumult as invigorating as it is maddening, typified by a breakneck pace of top-tier hires and a sense that the firm is ready to shift course at a moment’s notice.

“I don’t run a highly structured company,” muses Richard Edelman, who likens the approach to “organized chaos.” The question remains: Is there too much chaos and not enough organization for an agency that wants to define the future of communication?

RE against the world

If it was not exactly a turning point, Richard Edelman’s decision against pursuing a deal with ad agency Droga5 probably marked the moment when the giant PR firm finally dispensed with its ambition of one day becoming a company that could rival mammoth holding groups like WPP or Omnicom Group.

There were certainly those within the agency who felt like such a move might make sense. After all, Edelman’s remarkable pace of growth regularly fuelled speculation that it would seek to broaden its service offering, by acquiring businesses beyond its traditional PR comfort zone.

The biggest prize, presumably, would be a major advertising agency. This was not an idle pursuit. The convergence of marketing and communications has placed holding groups, led by aggressive WPP CEO Sir Martin Sorrell, in pole position as companies increasingly look for solutions that reflect the overall consumer experience, rather than outdated channel-based siloes.

Amid this emerging reality, Edelman ran the risk of being exposed; if it couldn’t offer all of the services a holding company could, it might find itself shut out of major public relations reviews. So the much-feted Droga5, an ad agency with a similarly feisty, independent creative streak, would have appeared the ideal fit.

Edelman admits there was pressure to “bulk up in advertising”, but then decided against taking things further with Droga5. “It wasn’t just about cost,” he contends, but the reasoning can be framed in economic terms. “To get to scale in advertising, and I think larger companies want us to scale, we would have to devote every available resource and more to doing that. Then you’re into at least $100m of acquisitions. It was beyond our reach.”

Edelman had also come to believe that it would distract the agency from its core purpose. “We had to look at whether our idea of building a PR-centric holding company was, in fact, the correct way to go,” he notes. The idea of offering everything under one roof became less appealing.

“It’s why I got into that tussle with Dave Senay,” adds Edelman, referencing his post earlier this year about FleishmanHillard’s repositioning. “FH wants to be a sole source supplier. I think we’re better off being Switzerland — an entirely neutral body.”

The truth is that both Edelman and Senay are not so far apart in terms of how they want their agencies to evolve. Both believe that hiring non-traditional talent, rather than acquiring new firms, is the best route to convergence. Edelman believes that his trump card comes from the partnerships his firm can form with ad agencies around the world, like the alliance it struck with India’s Rediffusion to win the mammoth Tata account.

“Unlike Burson, we can actually partner with local ad agencies,” says Edelman. “That gives us tremendous advantage when qualifying for, for example, a government contract.”

Trying to provide consulting and advertising services, admits Edelman, did not work for the agency. Yet he remains convinced that a public relations firm — and he is insistent about retaining that label rather than opting for the more fashionable communications tag — can prosper in the ‘convergence era’.

“We’re now able to get into budgets which we weren’t before, with CMOs and with digital,” he contends, pointing to the firm’s work with Pfizer, Adobe and Port Metro Vancouver as examples. “Our creative is what I call ‘fast-twitch’. I feel so strongly that the industry can take share of the total spend.”

Different folks

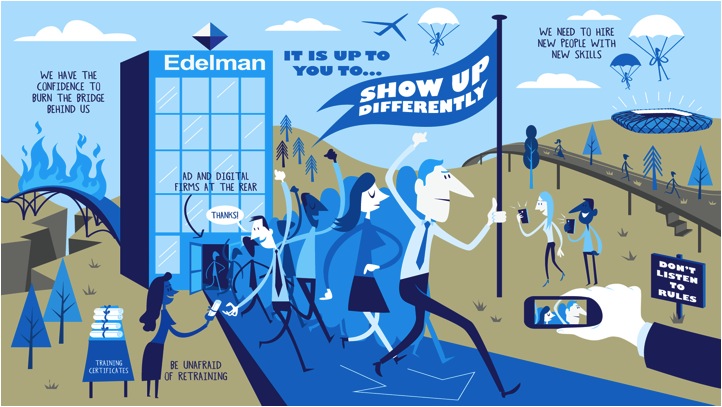

None of this necessarily counts as novel thinking, even if Edelman’s impatience with the current state of affairs is clear. To really fulfil their CEO’s ambition of “leading the industry breakout”, an Edelman insider notes that the agency is trying to lessen its reliance on PR agency convention — whether by hiring non-traditional talent, developing a creative newsroom or mulling a radical restructuring.

All of which explains the ‘Hamburg Principles’, the rather grandiloquent title that suggests a United Nations initiative but is instead Edelman’s five themes for agency growth. Spanning creativity, research, digital, partnerships and media, what is clear is that executing the strategy will require substantial investment in “new people with new skills”.

As with many of its rivals, that is already happening at Edelman, whether it is paid media specialists, planners or creatives. “What we’re quietly doing is picking up media buyers and media planners,” says the agency insider. “Our planners and creatives are getting better and better. We’re not first rank creative directors, but we are top of the third level.”

Making those hires is one thing, but integrating them successfully into the agency is quite another. Edelman’s success with ‘trophy hires’ is mixed, particularly when it comes to people that do not bill in the same way as traditional PR fee-earners. Richard Edelman remains adamant, for example, that everyone has to handle a significant proportion of client work, an attitude that does not always mesh with, for example, the high-priced creative and planning directors of the world.

“You may call me old-fashioned,” asserts Edelman. “If you don’t [do client work], then you have no business being with us. I’m billable 33% of the time.”

Edelman believes that client work makes his people “inordinately practical” and is “core to the culture”. Although he doesn’t mention it, it also ensures they make money. But not everyone at the agency is convinced that this approach always makes sense.

“[Richard] knows that’s not the case anymore,” says the senior executive at the agency, when asked whether everyone should be a fee earner. “Creative directors and planners are very hard to bill in the same way.”

Digital divide

So, presumably, are digital people, which leads us to the critical element in Edelman’s operations. Much of Edelman’s growth over the past decade has been powered by its highly successful Edelman Digital unit, which now clocks in at more than $110m and is probably the best example of the firm’s entrepreneurial culture.

“Edelman historically has been successful in taking calculated risks that pay off, and I give them a lot of credit for that,” says Heather Mitchell, head of global PR and social media for Unilever’s hair care category. “They were my first agency partner to invest in and build a social media capability and they have grown it into a successful business model that not only wins awards, but more importantly, wins consumers' attention.”

In common with other successful digital agencies, the business is run along more of a project model than the classic PR retainer structure and also draws much of its earnings from marketing and digital (rather than communications) budgets.

Yet Edelman Digital’s standalone status has sparked concern that its growth is overshadowing the remainder of the business, which has expanded at a more sedate pace, in line with the overall industry average. Agency sources estimate that around a third of Edelman Digital’s business is shared with the main firm, a fact that has perhaps helped prove its bona fides to a digital community that might ordinarily be wary of a traditional PR shop.

“They should integrate and separate, not just integrate,” says the Edelman insider. “Digital people will not join a PR company. They want to join a company that is doing fantastic technological and creative projects. They are smart enough to know they should do that within the confines of a PR company but they want their own structure and titles.”

The notion that Edelman Digital’s ‘separation’ from the main PR firm is a good thing has proved controversial. The pressure for an integrated firm that can seamlessly service digital, social media, community management and more traditional PR activity is difficult to avoid; it appears to be the driving force behind every public relations agency’s business development strategy. More broadly, it reflects the convergence of different media channels and the moves by advertising and digital agencies, for example, to build a stronger ‘earned media’ presence.

For Edelman, more prosaically, it might also suggest a troubling lack of cohesion. It is telling that Richard Edelman devoted time at Hamburg to the idea of ‘Digital Edelman’. While Edelman Digital has grown rapidly, it has largely steered clear of infusing its skills among the remainder of the agency. Edelman himself admits that the main firm is still not “digital enough”, explaining the current rollout of an agency-wide training program.

However you look at it, the situation suggests a digital divide. More than one source interviewed for this story suggested that Edelman Digital could spin off from the main business. Staffed with numerous digital hotshots, there is no reason to think it would not be a success, in the manner of Social@Ogilvy, which sits within the massive Ogilvy & Mather group but retains a separate presence. Richard Edelman, unsurprisingly, is buying none of it.

“It is totally antithetical to the strategy,” he contends. “It may suit Ogilvy because they have the advertising and PR firm. I think our approach is smarter. Basically Ogilvy is ignoring the top two parts of the (media) cloverleaf, which is mainstream and blogs.”

“Richard has always been very clear externally and internally that we are one company in PR, digital and research,” says an Edelman insider. “They get their client leads out of Edelman. [Spinning off] was never an option or an opportunity.”

Organized chaos

The situation may simply reflect the internal politicking that, for better or worse, remains a feature of life at Edelman. At most of its rivals, high-level discussions over the future course of the agency are unlikely to become as public. Other global PR networks are evidently more buttoned-down, certainly less leaky and probably better at managing senior-level turnover.

But Richard Edelman appears to like it that way, noting that he finds the debates “energizing”, even if it can sometimes suggest a business that is in a perpetual state of flux. “He quite likes everyone telling him what to do,” says a senior executive at the firm. “Richard sets the course. We’ve got a new focus now, but it hasn’t felt like a schism.”

It is a state of affairs that is likely influenced by the firm’s origins. “We were very shy about becoming the biggest PR firm, whenever it was,” Edelman tells the Holmes Report. Even the agency’s long-term goal is a source of discussion, given that the possibility of a sale is remote, and the prospect of becoming the world first billion-dollar PR firm is dismissed as an “outcome.”

Instead, Edelman says he wants to be a “reference point for how smart marketers are playing that game.” It is the kind of talk that is popular with PR agency heads big and small, calling for the industry to realise a more central brand-building role by redefining prevailing views of PR practice.

Asked why Edelman has resisted the trend towards rebranding as a communications firm, the 59-year-old notes that “PR is actually an attitude, not just a service line.” You could probably say the same thing about the firm that he is now in sole control of. In many ways, the Edelman attitude — paranoia and all — has helped to set the PR industry agenda over the past decade. Continuing that success over the next 10 years, while protecting market share and retaining a culture of innovation, is a daunting challenge. Still, set against a backdrop of dramatic business change and reinvention, perhaps Edelman’s ‘organized chaos’ is not such a bad idea after all.

.jpg)

.tmb-135x100.jpg)

.tmb-135x100.jpg)