Marian Salzman 29 Jun 2015 // 7:15AM GMT

Does anybody still wait patiently for the next edition of the newspaper to get their news update? That’s a matter for debate in some households I know, but let’s go with the flow and say probably not too many people.

Does anybody check the clock for a scheduled TV or radio newscast to get the latest news? Come to think of it, how many people trust the news only when their favorite journalist from their go-to news media brand delivers it? It’s tempting to answer “nobody under the age of 60” to all these questions, but that’s doing a disservice to legions of switched-on over-60s.

Old-style traditional media and news-consuming habits are still out there, just like mom’s cooked-from-fresh-ingredients dinner is still out there somewhere. Actually, that somewhere might well be mainly in the minds of some PR and advertising professionals who know that the world has changed but who still feel more comfortable with old familiar images of American life.

No wonder. For anyone over 35, it seems like forever ago that the traditional media was our go-to news outlet. It had a virtual monopoly on mass-market audiences. It owned newsgathering, it owned the stories and it owned news-hungry audiences, which was pretty much everybody. News brands and their journalists owned credibility and trust. That meant that the PR industry had little choice but to rely on traditional news media to reach news audiences.

Now traditional news gatekeepers and waiting for news are becoming history for the 40 percent of the world’s population who use the Internet (and as high as 85 percent to 90 percent in countries like the U.S., U.K., Japan, Germany and France). Whatever the news might be, it’s online somewhere soon after it happens, so it’s just a matter of finding it when and where you want it. It will be on the websites of traditional news brands, or on startup news sites such as Vox or Breitbart, or on citizen journalist sources such as Global Voices and Examiner. It might even be on individuals’ blogs. (And besides journalism, let’s not forget native, where you pay to weigh heavy in prospective readers’ reading zones.) No matter. People have become savvy at finding news when they want it and curating their own news mix to satisfy their own personal needs.

This is part of what has made Facebook the second-biggest source of government and political news (48 percent) in the United States, just a point behind local TV news (49 percent). It’s not that people log in to Facebook as a news channel in the traditional sense. It’s that news is part of the mix of information they share with their contacts, along with kitten videos, jokes, vacation photos and selfies. It’s like part of the air they breathe.

Here’s more of what we’re seeing in the U.S. in terms of the news landscape, which is apparent in many countries worldwide: More-traditional Americans still have a hierarchical attitude toward news sources, seeing long-established legacy news brands in the journalistic heights and newcomer newsy bloggers down in the swampy lowlands. But for less-traditional Americans, the news landscape is much more egalitarian, accessed through the latest technologies, especially mobile devices. It shares screen real estate with entertainment and communication, with personal and professional content.

To use Thomas Friedman’s insight into globalization, today’s news media world is flat. Dwindling numbers of salaried staff journalists employed by legacy media brands are slugging it out with growing numbers of citizen journalists competing for audience attention. “Citizen journalist” is a deceptively simple phrase—it covers everybody from a lucky bystander with a camera phone all the way up to dedicated bloggers with a passion for a particular subject, whether food trucks, fashion or pharma.

The terminal decline of traditional media and the rise of citizen journalism has a whole lot of implications for PR professionals. First: the sheer challenge of keeping up with who’s who. Anybody with opinions, an Internet connection and time on their hands can make big quickly. A bigger challenge for PR is figuring out who among all the names really matters to the relevant audiences. Which citizen journalists have profile, traction and influence? Above all, who has momentum? On one hand, PR runs the risk of wasting scarce resources on cultivating relations with citizen journalists who look impressive but are on a fast track to nowhere. On the other hand, there’s the risk of missing out on small players who have what it takes to garner big influence.

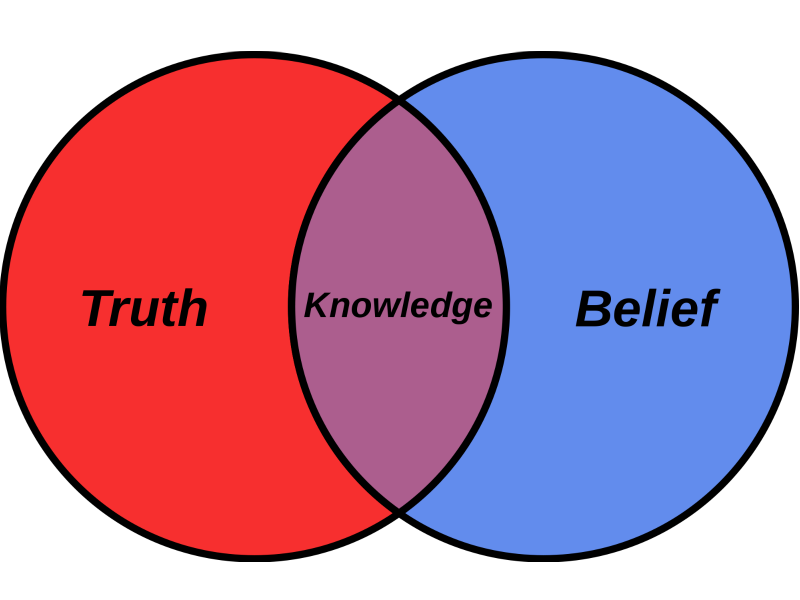

Then there’s the issue of whom audiences trust. Favorable coverage by traditional media used to be the gold standard of credibility until pay-to-play debased the currency. Now citizen journalists are becoming not only content creators but also the trusted and unofficial reputation managers for brands. It will take fine judgment by PR professionals to figure out the potential of these new players. Do they want to be impartial commentators on the brand and its industry? Do they want to stay independent but get scoops from the brand? Do they want sponsorship or some form of privileged relationship with the brand?

In the age of citizen journalism, PR professionals need to transform their media relations skills from the checkers of traditional news media to the three-dimensional chess of media in the networked world.

Marian Salzman is CEO of Havas PR.

.jpg)