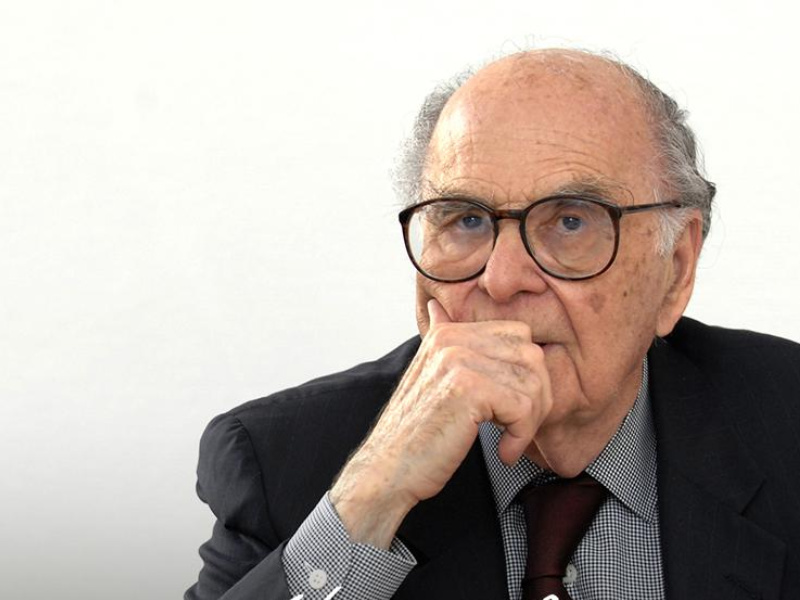

Paul Holmes 12 Jan 2020 // 5:09PM GMT

I first met Harold Burson when I was a reporter for PR Week, based in London. It was 1985, which meant that Harold was in his early 60s and Burson-Marsteller was the largest public relations firm in the world.

Not just the largest, but also the best. I told him that I had visited Burson-Marsteller offices in half a dozen countries, in Europe and America and Asia, and that I had been impressed by the consistent quality of the firm’s senior people. If you had put me in a room with a dozen PR people in any of those markets, I told him, I would have been able to pick out the Burson-Marsteller person in five minutes.

He liked that, and we talked about the critical role that recruiting, nurturing and retaining top talent played in building a great public relations firm. That’s conventional wisdom these days, but it was not a view universally shared by Burson’s competitors (he didn’t really have any peers) back then. It was one of many ways in which Harold was ahead of his time.

He was proud of his people, and especially of his firm’s commitment to training—Burson-Marsteller provided a talent pool for itself and many of its competitors, investing in professional development at a time when few others recognized the value, and when some feared it would simply lead to other firms targeting their employees.

He also wanted to talk about research: Burson-Marsteller was one of the first PR agencies to formalize the research function, and was using data to develop strategy and to measure the impact of campaigns.

A couple of years later, I visited Harold in his offices in New York, at 230 Park Avenue South, and he walked me around the 13th floor, where many of the firm’s senior executives resided. I don’t remember who I met that day, but the offices there housed people like Buck Buchwald, James Dowling, Jim Lindheim, Bob Leaf, Tom Mosser, Stan Sauerhaft, Al Tortorella—giants of the industry, most of whom I knew only by reputation.

I sat down with Harold in his office for a lengthy conversation that spanned the firm’s international growth—he was proud that BM leadership was becoming increasingly international, with indigenous talent leading local offices—and about his broad definition of public relations, and its role in influencing opinions and attitudes.

The resulting article also included a comparison between Burson and Yoda, who had made his first appearance in The Empire Strikes Back a couple of years earlier. I called Burson “wizened” and “wise” (like the Jedi knight) and there were some at PR Week who thought he might be insulted. Instead, he sent me a hand-written note (a thing people did back then) thanking me for my time and for the comparison. He had a sense of humor.

Over the ensuing years, I was to learn that Harold was one of the most accessible executives in the business. He sometimes answered his own phone, he always returned calls, and he often made time to meet with trade reporters—usually without any agenda beyond sharing his knowledge and perspective.

One of the things I learned from Harold (that’s what everybody, from secretaries to competitors, called him) was that you could be a demanding CEO, a true professional, and at the same time a thoroughly decent human being. I never heard him bad-mouth a competitor. And he never blustered or complained when coverage of his firm was less than positive.

He was equally generous—likely even more so—with his own people. Writing at the site BCW set up to memorialize Harold, an anonymous employee recalls: “Even as a junior newcomer, I was welcome to call him, to stop by his office, to send him a note. Harold would patiently answer your client questions, and you can imagine the value of having been able to tell a troubled client that you were sharing Harold’s view.”

And he helped numerous competitors and agency leaders. People like John Graham (as he built FleishmanHillard into a global leader, and ultimately the firm that would take Burson-Marsteller’s place as the industry’s most admired) and Lou Capozzi (as he took the helm of Manning Selvage & Lee during its most impressive growth phase) were frequent guests of Harold’s at his favorite Gramercy Park lunch spots.

“He was a living legend and you would often see him surrounded by throngs of people, mainly young professionals at various public relations industry events,” Graham recalls. “He could have stood on a pedestal and told the world “how to get it done” but that was not Harold. He was humble, modest, gracious but always precise and forever one to offer a suggestion with a smile…. I always enjoyed our occasional lunch conversations whether we were discussing trends in our industry or world events. I never stopped learning from this great man.”

Adds Capozzi, “Lunch with Harold was always great…. The last time I was in his office, when he was over 90, he had to apologize for taking a call from a client’s CEO….. He never failed to surprise me with his energy and insights.”

His willingness to give time back to the industry was a constant. He was also on my first ever awards jury—a four-person panel that also included Dan Edelman and Johnson & Johnson communications chief Larry Foster—back when the magazine I wrote was called “Inside PR” and our awards were called the CIPRAs (Creativity in Public Relations Awards).

He accepted the invitation without hesitation, did the work even when it turned out to be more onerous than I had intimated. And of course, he gave the competition instant credibility. And his insights into what made a great campaign—particularly his insistence on actual business results—continue to inform the SABRE judging process today.

As generous as he was with his time and his knowledge, Harold never wavered in respecting the confidentiality of his clients. For many years, he resisted calls to tell the inside story of the crises and corporate decisions he had worked on (the Tylenol recall probably the most prominent among them), citing the need for clients to be confident that their decision-making processes would remain private, and reluctant to exaggerate his own role in what were almost always collaborative efforts.

His book, The Business of Persuasion, published just a couple of years before his death, did little to satisfy the hunger for inside info. A fascinating history—especially when it comes to his involvement in the Nuremburg trials, which he covered for army radio—and full of insights into his approach to both business management and client counsel, it was nevertheless bereft of the kind of sensational revelations that might have made it a best-seller.

It did, however, underscore how much he shaped the modern public relations industry in general, and the agency business in particular. The model he developed, creating specialized practice areas in fields such as crisis management, public affairs, and investor relations, and focused industry sectors such as healthcare and technology; his approach to international expansion, with offices in major foreign capitals; his creation of a matrixed organization unified by a core set of values and defined by the character of its CEO—was followed by all of those who came after him.

And he was a thinker about the profession, emphasizing the importance of ethical practice and of treating public relations as a management discipline.

In a speech to the Institute for Public Relations Research and Education in October of 2004, he offered his definition of public relations as the “discipline that helps reconcile institutional or individual behavior in a manner that accords with the public interest and, when effectively communicated, creates opinions or attitudes that motivate target audiences to specific courses of action.”

The critical part of that definition is that “there are two components that comprise public relations: one is behavior, the other is communications.” Of the two, he clearly saw corporate behavior as the most important: “Our job as public relations professionals is two-fold. It is to help our clients or employers fashion and implement policies and actions that accord with the public interest.”

I discussed the proper role of public relations with Harold many times: he might have been the only person in the industry who hated the term “communications” as a synonym for or alternative to public relations more than I did. Communications was a part of his job, sure, but it was not the most interesting, or the most important. Harold advised his clients on what they should do, not just what they should say.

The only issue on which we disagreed substantially involved the enthusiasm for licensing of public relations professionals that he developed toward to the end of his career. In 2006 he told an ICCO conference in Delhi, “I cannot think of a profession that is not government licensed. Medicine, law, accountancy, engineering, architecture—all are licensed… I have often wondered if the status of public relations would now be different had it been licensed twenty or so years ago.”

I could not and do not share his enthusiasm for licensing, but our disagreement was mutually respectful and he came closer to persuading me than anyone else (and I had the same disagreement with Ed Bernays, 20 years earlier). And of course, the discussion was indicative of the fact that Harold continued to think about the profession and worry about its status, and to participate in his business, long after he stepped aside as CEO—he was still showing up at BCW’s offices three days a week until his move back to Memphis last year.

In recent years, all the conversations I have had with others about Harold Burson started by acknowledging his innate decency. Everybody who knew him, it seemed, had a story about how generous he was with his time, and his sage advice.

Said Donna Imperato, now global CEO of Burson Cohn & Wolfe, “He was the wisest person I knew, with the highest level of integrity, humility and kindness. Harold inspired tens of thousands of public relations and communications professionals around the world. His values and affinity for life will always be the core DNA of Burson Cohn & Wolfe. It has been my extraordinary privilege to have known Harold Burson as a colleague, a mentor and a friend.”

But Harold was also an exceptional businessman. He built the firm he founded back in 1953 into the world’s first truly global public relations agency and a model for all who followed. And he was a first-rate public relations counselor, who understood that corporate reputation was the result of corporate behavior, not communications, and who consistently advised his clients to do the right thing, not just say the smart thing.

For all of those reasons, Harold was a giant of the industry. Future professionals will not have the opportunity to meet him, but whether they know it or not, they will be influenced by his thinking.

.jpg)