Bob Brody 08 Jan 2021 // 12:13AM GMT

About 25 years ago, Howard Rubenstein, who died the other day at age 88, dispatched me to meet a long-standing client of his named Robert Ross. An entrepreneur, Ross looked like a cross between the English actors Sidney Greenstreet and Robert Morley. He operated an off-shore medical school called, modestly enough, Ross University. Now, Ross told me, he would be venturing into healthcare products. He planned to introduce to the world a homeopathic snoring medication from China, a nasal spray called Y-Snore.

Somehow, I soon got the idea to research who might currently be the world’s loudest snorer, and naturally checked the Guinness Book of World Records. This distinction belonged to one Melvin Switzer, who lived in Dibden, England. I reached out to Melvin to ask him to try Y-Snore -- and, if it proved satisfactory, to publicly endorse it. Melvin immediately agreed.

A few weeks later I phoned Melvin to learn the outcome. The nose drops had worked, he told me emphatically. He snored much more quietly now. Then Melvin put his wife on the line. Yes, his long-suffering wife said, verifying his account. In fact, she revealed, the nose drops had enabled her to sleep through the night for the first time in years.

Perhaps now, as a newcomer to Howard J. Rubenstein Associates, I would be redeemed. I’d gotten off to what we’ll charitably call an iffy start there. My first client, shortly after meeting me, asked me off the account. I fared little better with my second and third, who by turns disregarded and altogether dismissed me. All I had succeeded in doing so far was failing.

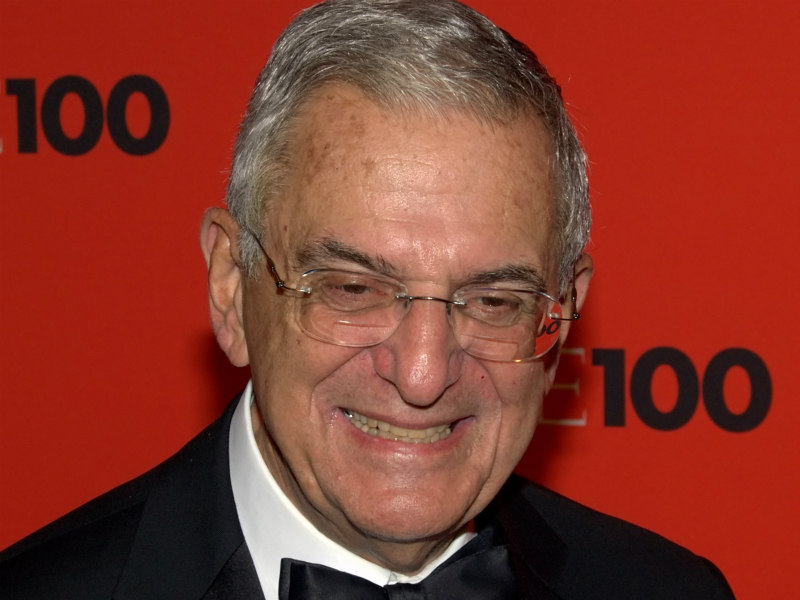

I wanted nothing more than to impress my employer. Howard Rubenstein was, after all, a local legend and then some. He opened his public relations firm at the age of 22 at a kitchen table in the apartment he shared with his parents in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. By the mid-1990s, he employed about 100 account executives, handled about 400 clients and earned an estimated $20 million annually.

Howard came to amass his power in the 1970s, primarily as an advisor to then New York City mayor Abe Beam. Howard went on to build lasting friendships with Ed Koch and other New York City mayors, guiding Mayor David Dinkins through the racially explosive Crown Heights episode. Governors and United States presidents trusted him, too. A photo shows Howard, ever the diplomat brokering peace among feuding parties, standing between a smiling New York Governor Mario Cuomo and a smiling New York City mayor Rudolph Giuliani, even though the two could barely tolerate each other.

He handled crises for Supremes lead singer Diana Ross (whose concert in Central Park prompted a mob to riot), talk show host Kathie Lee Gifford (whose clothing line came about courtesy of sweatshops) and Sarah Ferguson, otherwise known as the Duchess of York, a k a Fergie (whose image he rehabilitated by securing her a role as a spokesperson for Weight Watchers, then a client). He had pulled off these feats with such finesse that Rudolph Giuliani had dubbed him the “dean of damage control.” Howard also had a flourishing specialty in real estate developers, representing, Harry Helmsley (and his notorious wife, Leona Helmsley, unforgettably dubbed the “Queen of Mean”), the Rudin family and – yes -- Fred and Donald Trump.

Clients often came in the door needing either to establish an identity or reinvent one, and Howard’s job was to tell the story that revealed the truth – and, if possible, even improved on it. If, however, a client had committed a mistake and now wished to save face, his job was – how to say? – to reconfigure reality a little. He mastered the art of turning mountains into molehills and molehills into mountains. These acts of perceptual alchemy called for stagecraft and brinkmanship of the first order.

As cases in point, media magnate Rupert Murdoch, who had migrated to New York City from Australia to set up operations at The New York Post, was by then a long-time client, too. So was New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, infamous for firing managers, including the beloved Yogi Berra. The clientele was a patchwork crazyquilt – music stars, local hospitals, authors, law firms, civic groups, universities and gung-ho entrepreneurs. It was democracy in action as all comers got a shot at the holy grail. Howard, as a strict matter of policy, appeared to have only two real entrance requirements for clients: a pulse and a check that cleared.

All around his office, the size of at least half a tennis court, Howard had photos of himself with the well-known. Howard with Robert F. Kennedy and Eleanor Roosevelt. Howard with police commissioners and dignitaries, royals and tycoons and movie stars. Here was Howard with Ronald Reagan, there with Pope John Paul. Howard with Golda Meir and Lee Iacocca and Dan Rather and Bob Hope and Prince Charles and Bill Gates and Reggie Jackson. Howard with VIPs at black-tie benefits, shoulder to shoulder with notables at press conferences and movie screenings, book-launch parties and political rallies. The gallery of photos, too numerous for the large room, extended out into the corridor and down the hallway. Forty years of Howard side by side with the famous, Zelig-like, his life apparently just one long photo op.

So it was that Melvin Switzer thereby officially became a spokesperson for Y-Snore. I approached a reporter at The National Enquirer to offer an exclusive. But the reporter would commit to coverage only if the newspaper could subject Melvin to a rigorous overnight snoring test in a hotel room, complete with microphones dangling over his bed to record his decibel level. This adherence to scientific method at a publication largely known for lurid accounts of Hollywood stars in distress and aliens from space landing in corn fields impressed and surprised me.

Melvin passed the test, and The Enquirer brought out a major feature with photos of him and the product. In short order, major supermarket and drug store chains, from Walmart to Walgreen, ordered shipments of Y-Snore worth millions of dollars. For once, a PR stunt had led to a measurable business success, and spectacularly so.

Our client, Robert Ross, was over the moon about it. Better still, he told Howard so. And Howard personally called me in to compliment me. And at our next staff meeting, he told everyone in our office the whole story, commending my creativity. The world’s loudest snorer put me on the map at his firm. And for that, and of course so much else, I humbly thank Howard.

Bob Brody, a public relations consultant and essayist in New York City, is author of the memoir “Playing Catch with Strangers: A Family Guy (Reluctantly) Comes of Age.” He is a former senior vice president at Weber Shandwick, Ogilvy and Rubenstein Associates.

.jpg)