PRovoke Media 19 Jan 2022 // 10:29AM GMT

You can find all of our annual Crisis Review coverage here

7. Yorkshire CCC is institutionally racist

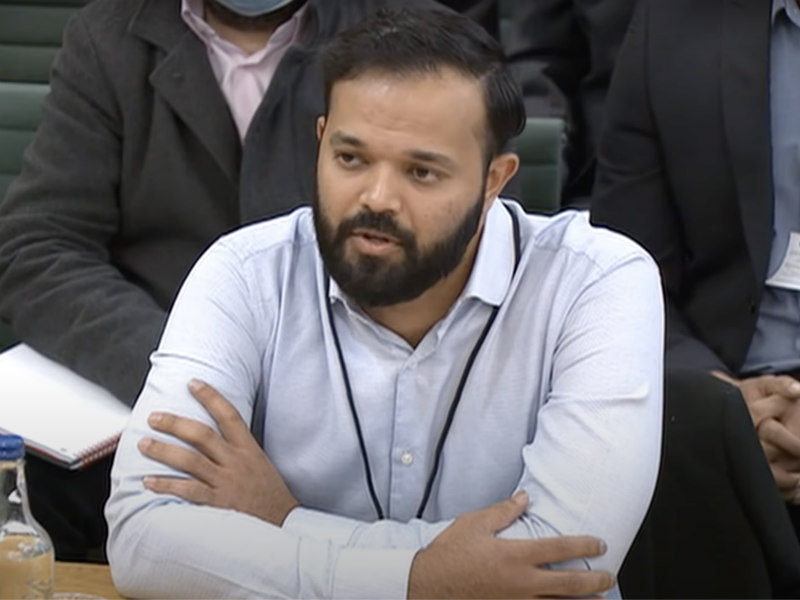

Former Yorkshire County Cricket Club player Azeem Rafiq first complained of racist abuse and bullying at the club back in 2017, but it was not until 2020 that an independent inquiry was launched. That itself reflected a remarkable lack of urgency on Yorkshire's part, which was only reinforced by the club's refusal to release the full independent report.

By then, the crisis had snowballed into an existential issue for Yorkshire CCC, with sponsors deserting the club as Rafiq delivered highly compelling and damaging testimony before the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) Committee, with many of his allegations about racism and bullying supported by other Asian players at the club.

"When I heard Azeem Rafiq's emotional and heart rending account to the DCMS Committee, of racism he experienced at YCCC, its impact on his mental health/career, it made me both sad and angry since this is the lived experience of many ethnic minorities across society," says the Purpose Room founder Sudha Singh, who also co-chairs the PRCA's Equity and Inclusion Advisory Council. "Azeem Rafiq faced racism at the club during his stint there over a period of a decade - so this was not an isolated incident but systemic and entrenched.

"YCCC's first failure was in its duty of care — their inability to listen to and look out for the welfare of Azeem Rafiq when he first made a complaint in 2017," adds Singh. "Little did they know that through their actions they were creating the right environment for a perfect storm."

As Singh points out, the approach of YCCC leaders, including chair Roger Hutton, CEO Mark Arthur and the club's board, reflected several communications failures, starting with a mentality that appeared rooted in a different era.

"It seems as though the YCCC leaders were living in a bubble, their approach reeked of arrogance — they believed that they could make it go away," explains Singh. "The second failure was that instead of responding with empathy, getting the leadership to engage with Rafiq and the broader community there is an attempt at victim blaming."

That included YCCC's claims that racism could be classed as "friendly banter", yet another sign that the club's leaders appeared unaware of how to address the toxic problems caused by racial discrimination. It soon emerged that the independent investigation was plagued by conflict of interest issues, and YCCC's eventual apology, with no further action taken, was viewed as shockingly inadequate given the magnitude of the crisis.

"The third failure is one of transparency and lack of will to do the right thing," says Singh. "There was absolutely no attempt to address the underlying issues or reach out

to other ethnic minority players or local clubs. It seemed as if the organisation would go

to any length to protect itself and those accused. But, all the prevarication damaged their

reputation seriously and led to key sponsors walking away."

Sponsors that walked away included Nike, Tetley's, Yorkshire Tea, David Lloyd Clubs, Harrogate Spring Water and Emerald Publishing. Hutton was widely criticised for his ill-judged response. Meanwhile the English Cricket Board did not escape the fallout either, with the UK Government questioning whether the body was "fit for purpose" given its apparent disinclination to get involved.

"[The ECB] missed a huge opportunity to show leadership on dealing with the racism issue in Yorkshire and using that as a trigger for a root and branch review of cricketing bodies in the UK," says Singh. "They deliberately chose not to get involved or use their convening power to take charge and lead, until they had to after it became clear that there would be no action from the investigation in Yorkshire. They were slow to respond, and only did so perhaps due to the mounting political pressure."

With public pressure mounting, including from UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Health Secretary Sajid Javid, heads soon rolled, including Hutton, director of cricket Martyn Moxon, and head coach Andrew Gale as Yorkshire replaced its entire coaching staff. However, new chair Kamlesh Patel will be keenly aware that Yorkshire has plenty of work to do if it's to rebuild bridges with the county's Asian cricket community, which it has marginalised for far too long.

"The YCCC, Professional Cricketers' Association and ECB were guilty of trying to maintain the status quo and reluctant to break rank on an important issue," concludes Singh. "I am also of the view that getting in an ethnic minority chair cannot be the quick fix solution, the problems are bigger than just replacing a white person with a visible ethnic minority leader. Courageous leadership, systemic reform, transparency, training and ability to continuously engage with communities and stakeholders is the way forward." — AS

8. Peloton: A tale of two crises

Peloton faced two very different crises last year: a major product recall and an unfavourable product placement. Both incidents saw its stock price drop sharply and put the company firmly in damage control mode, but each was handled very differently.

The first incident came in the spring, when Peloton recalled its Tread and Tread+ treadmills in the US and UK after safety issues following investigations by a US watchdog, including the death of a six-year-old child and multiple reports of injuries. In March, CEO John Foley underplayed the incident, said the child’s death had been a “tragic accident” that was one of a “small handful” of incidents. But by May, when the recall was finally ordered, Foley admitted the firm had got it wrong: “Peloton made a mistake in our initial response to the Consumer Product Safety Commission's request that we recall the Tread+. We should have engaged more productively with them from the outset. For that, I apologise.”

In regard to the product recall, Kemi Akindele, WE Communications’ director of corporate reputation and brand purpose, reminds us that when crisis response is reluctant or slow, brand equity can erode fast: “This is especially true for a brand like Peloton that generates so much demand and desire. Peloton’s decision to continue advertising and its delay in recalling the Tread+ and Tread treadmills was a missed opportunity to put the safety of customers first, take control of the narrative and gain trust.”

Akindele’s assessment is that confronted with this first crisis, “Peloton did not remember to put customers first” — especially crucial considering it is in a 'brand love' relationship with its users.

By December, however, Peloton appeared to have learned its lesson. Its swift response to the character Mr Big dying of a heart attack on a Peloton bike in the highly-anticipated Sex and The City reboot, ‘And Just Like That’, certainly got people talking, as Mr Big actor Chris Noth appeared in an ad, voiced by Ryan Reynolds, underlining the benefits of regular exercise, just two days after the premiere that had led to Peloton’s share price immediately falling by 5%.

“Peloton had power and money behind its clever comeback, but it did not stand alone in response to the reputation damage,” says Akindele. “Although we may not all have Ryan Reynolds on speed dial to come to our rescue, as one part of your crisis strategy you should make sure you’ve got your own ‘star power’ to call on when you need. Stakeholder mapping to identify credible advocates, experts, supporters, and champions is crucial. These strong relationships allowed Peloton to respond quickly and cleverly to the storm, initially leaning on health and fitness experts to point to the lifestyle habits of the fictional character via a public statement.”

Peloton must have thought it was out of the woods at this point, but the crisis still wasn't over: just days later, the brand immediately pulled the ad after Noth was accused by two women of sexual assault.

In this case, Peloton also said that the movie’s producer, HBO, did not disclose the wider context surrounding the scene to Peloton in advance. But as Akindele notes, “Is it worth risking your reputation and public trust for sales? It’s understandable that Peloton would not want to miss this huge cultural moment but its important for brands to insist on knowing all the details before agreeing product placements or sponsorships.”

Summarising the impact of the most recent crisis, Akindele says: “Peloton took a risk and was able to play with death because no-one really died, this time. Understanding the external context and where your brand reputation is at that moment should guide your response. If this happened earlier in the year, following Peloton’s delayed product recall, I’m not quite sure the response would have been as favourable and in fact would have come across as tone deaf. If there’s a situation that relates to personal loss or safety, then you must get that emotionally intelligent response right.” — MPS

9. Basecamp and Coinbase grapple with politics in the workplace

Last spring, Basecamp CEO Jason Fried announced the software company would be banning “societal and political discussions” at work, as well as eliminating “paternalist benefits” such as continuing education and the company DE&I group.

“Today's social and political waters are especially choppy. Sensitivities are at 11, and every discussion remotely related to politics, advocacy, or society at large quickly spins away from pleasant,” the company wrote in a blog post. “You shouldn't have to wonder if staying out of it means you're complicit, or wading into it means you're a target. These are difficult enough waters to navigate in life, but significantly more so at work. It's become too much. It's a major distraction. It saps our energy, and redirects our dialog towards dark places. It's not healthy, it hasn't served us well.”

The move didn’t go well, to say the least. Within days, roughly 20 Basecamp employees — more than one-third of the staff — announced they’d be leaving the company, which offered packages to employees leaving the firm due to the new policies. The communications around the move, staff said, wrongly depicted the company as rife with partisanship discord. Pundits criticized the move for curtailing speech.

None of which should have come as a surprise to Fried, as the previous September Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong had a similar crisis on his hands after banning political speech, and giving employees a week to abide by the new rules or leave the cryptocurrency company. This after employees staged a work stoppage earlier in the year in protest of Armstrong’s handling of Black Lives Matter following George Floyd’s murder, one of a list of grievances among Black employees.

More than 60 employees, roughly 5% of Coinbase’s workforce, took Armstrong up on his exit offer and left.

You could blame the crises that blew up at both companies in part on Fried and Armstrong missing some of the fundamentals of successful internal communications, like creating inclusive company cultures and preparing employees for change versus issuing edicts. “Companies making these types of announcements must have an effective internal and external communication plan, especially in a time where social justice issues are a priority for so much of the workforce,” said Clyde Group VP Jenny Wang.

But these lapses run deeper, so much so that they serve as case studies in limiting free speech. And on a practical level, critics say curtailing discussions at work isn’t even feasible given that there is no hard and fast way to define what is or isn’t political speech and, with remote working, where work ends, and home begins.

“Politics now is everywhere,” said Levick chairman and CEO Richard Levick, adding that once innocuous issues — driving gas-powered cars and wearing a mask among them — now have political overtones. — DM

10. Activision Blizzard's "frat boy culture"

In July 2021, the state of California officially took on Activision Blizzard, filing a lawsuit accusing the gaming giant of having a “frat boy” culture rife with sexual harassment and discrimination against female employees.

And that was one of a slew of reputational blows Activision was hit with last year, as victims and advocates waged a high-profile battle against the company. After the California Department of Fair Employment & Housing sued Activision, hundreds of employees at the company’s Irvine, California headquarters walked off the job to protest the “sexist culture,” which the DFEH documented over a two-year investigation.

In August, the DFEH expanded its anti-discrimination lawsuit, alleging Activision Blizzard obstructed its investigation. Victims went public with stories of incidents such as inappropriate touching and comments about their bodies, as well as superiors asking them to have sex.

Then in November, the Wall Street Journal reported that CEO Bobby Kotick knew about the sexual misconduct charges for years, pushing Activision Blizzard stock down to its lowest in a year. There have been calls for Kotick’s removal ever since.

“It’s a sad situation but not unsurprising,” said Taylor senior VP Sabrina Lynch. “When you look at gender representation and objectification of the female form in games for consoles, mobile or online platforms, you can see that conscious decisions are being made to perpetuate a harmful gaze. When that gaze is engrained in the psyche of a pool of employees, it will show up in other ways — namely your work culture.”

Imre SVP of earned Stephanie Friess agreed, saying the toxicity of Activision Blizzard’s culture reflects a larger problem in the male-oriented gaming industry where “sexism continues to run rampant.”

“The Activation Blizzard scandal put a spotlight on an industry that has been mainly silent for decades regarding the respect and treatment of female employees. What made this scandal different was that the female employees of Activation Blizzard refused to be silent — holding the company accountable in a very public way,” she said.

So far, that accountability has included Activision, whose biggest titles include Call of Duty and Candy Crush, firing 37 employees and disciplining 44 others over the sexual misconduct allegations since July. The company also paid $18 million toward victims compensation in a settlement with the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which filed a civil rights complaint against Activision.

But, as we learned Tuesday morning, Activision may have found its savior of sorts in Microsoft, which is buying the game publisher for nearly $70 billion— the computing giant’s biggest acquisition ever. A few hours after the deal was announced, the Wall Street Journal reported Kotick is expected to give up his CEO seat.

“Microsoft is one of the few companies that could clean up Activision Blizzard’s mess,” said Levick chairman & CEO Richard Levick, adding that Activision “clearly couldn’t manage their way out of this crisis.

“They needed the money, the leadership and the courage of Microsoft,” Levick said. “Not every company is guaranteed to fail their way to the job.” — DM

11. Delta bungles its SB202 response

In March of 2021, a few months after corporate America had provided support for diversity and inclusion during the Black Lives Matter movement and a few weeks after many companies had pledged not to provide financial donations to legislators who had supported a violent uprising designed to overturn election results, an issue came along that brought together the two issues—systemic racism and protecting democracy. And somehow, companies managed to find a way to fumble their response.

Having found no evidence of voter fraud in the state’s presidential election and Senate run-off, Georgia Republicans realized that their best way forward was to create a new set of obstacles to legitimate voting. The result was SB202, a measure that allowed the Republican-dominated state legislature to take over elections and potentially disqualify Democratic voters.

Critics quickly pointed out that large corporations had provided plenty of financial support to the lawmakers who passed the measure. One of Georgia’s largest employers, Delta Air Lines, found itself on the front lines, with protests at its main terminal at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and calls for a boycott. With #boycottdelta trending, CEO Ed Bastian said the company had “engaged extensively with state elected officials in both parties” to “improve” the law.

As it became apparent that such a weak response was not going to appease anyone, Bastian wrote a letter to employees acknowledging that the law will make it harder for Black Georgians to cast their votes and calling it “wrong,” adding that it was “based on a lie” that there had been rampant voter fraud in the 2020 election.

State Republicans responded by revoking a tax break on jet fuel. Voting rights activists, meanwhile, wanted the company to go further, by pledging that it would not make donations to those who had passed the law—which the company declined to do.

At no point was there any sense that Delta was drawing on its values—or any values—in its approach to the crisis. Every decision appeared to be a reaction to external pressure, from voting rights advocates or from Republican lawmakers. The on-the-fence response failed to satisfy anyone. As LaTosha Brown of the group Black Voters Matter said, ““Either you’re for supporting voting rights or you’re against it. There’s no gray area.”

Added crisis expert Richard Levick, “They are going to have to realize that issues regarding race, access, democracy are things where there's an expectation of their involvement or at least not their involvement on the wrong side.” — PH

12. Southern Water causes a stink

Last summer, Southern Water, one of the biggest privatised water companies in the UK, was fined a record £90 million for deliberately dumping between 16 billion and 21 billion litres of raw sewage into the seas around the south of the UK between 2010 and 2015, in what was called the “worst environmental crime in the 25-year history of the Environment Agency.”

The judge who ruled on the case was damning, saying the offences showed a “shocking and wholesale disregard for the environment… and human health”. Southern Water had ignored 168 cautions, continuing to run wastewater treatment works at below capacity to save money and, instead of treating the sewage as required by law, stored it before discharging into the protected waters, with “long term corporate knowledge,” according to prosecution lawyers. The company’s attitude to the investigation was also problematic, said the judge, with co-operation that was “grudging, partial and inadequate.”

Southern Water’s response to the fine was, however, contrite, with chief executive Ian McAulay – who had joined the firm in 2015 – saying he was “deeply sorry for the historic incidents”. In his statement, he said: “I know that the people who rely on us to be custodians of the precious environment in southern England must be able to trust us. What happened historically was completely unacceptable and Southern Water pleaded guilty to the charges in recognition of that fact.” He said the company had changed its practices and also underlined that customers would not bear the costs of the fine.

Gavin Devine, founder of public affairs firm Park Street Partners, believes that in communications terms Southern Water did the best it could in response to a fine for what had clearly been a deliberate policy of discharging untreated waste water into the sea over many years. “The chief executive was front and centre and didn’t try to hide the seriousness of what had gone on. And his key message – that these incidents happened more than five years ago, before he personally had joined the business, and the company had changed – came through loud and clear in the media coverage.”

Devine says the case also showcased one of the challenges of holding water companies to account: “Even if Southern Water had fluffed its response and the public had been outraged, what could they have done? They would still need water (and sewerage) and they would have nowhere else to go. The company isn’t listed, so it’s not like its share price took a hit; its private investors will not have been happy to stump up £90 million, but that’s not really a comms issue. There may be some issues with keeping and finding staff, but my guess is that will probably blow over.”

All in all, Devine says that, as a case study for crisis communications, this was not too unsavoury: “Showing leadership, apologising openly and distancing yourself from the past are important parts of responding to most crises. To that extent, the Southern Water comms team can feel good about their response.” — MPS

13. Hyatt repudiates Nazism

Like it or not—and most companies very definitely come down on the “not” side of the discussion—there is no such thing as neutrality any more when it comes to the political world. Failing to take a stand is interpreted as an endorsement of the status quo, and any indication of cooperation makes your company vulnerable to a boycott.

So the chances are that Hyatt would have faced some criticism just for hosting last year’s Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) at the Hyatt Regency in Orlando, Florida.

But the crisis was taken to a new level after observers noticed that the event’s stage design bore a striking resemblance to a Norse rune adopted by Nazis in an “attempt to reconstruct a mythic ‘Aryan’ past,’” according to the Anti-Defamation League. Calls for a boycott of the hotel chain quickly ensued.

Hyatt’s initial response appeared to miss the point: “We believe in the right of individuals and organizations to peacefully express their views, independent of the degree to which the perspectives of those hosting meetings and events at our hotels align with ours,” said a company spokesperson—a position that might have made sense if the company was defending CPAC speaker Donald Trump’s claim that he had really won the previous year’s election, but seemed woefully inadequate in response to Nazi symbolism.

But as criticism mounted, the company appeared to recognize that something stronger was needed and said that it took concerns “about the prospect of symbols of hate being included in the stage design at CPAC 2021 very seriously as all such symbols are abhorrent and unequivocally counter to our values as a company.”

While CPAC was quick to accuse Hyatt’s stance as a part of so-called “cancel culture,” a much more serious crisis was averted. — PH

.jpg)