Paul Holmes 12 Feb 2024 // 3:17PM GMT

It is now almost 30 years since protests against the environmental impact of Shell’s operations in Nigeria prompted a violent reaction that culminated in the execution of writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other men, who would become known collectively as the Ogoni Nine.

The fact that 30 years later, Shell is still feeling the reputational — and legal — fallout from those events should serve as a reminder to executives at Del Monte, which currently finds itself embroiled in a crisis that has some eerie echoes of the Shell Nigeria case, that stories of corporate complicity in murder and mayhem can be both global and long-lasting.

The History Lesson

Oil was first discovered in Ogoniland, a region in southern Nigeria, in 1957. The Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People was founded in 1990 by Saro-Wiwa and other Ogoni leaders in response to the degradation of the Ogoni land by the Shell Petroleum Development Company and the unequal distribution of oil revenues by the Nigerian government.

At the time, Shell was by far the largest multinational in Nigeria, pumping almost a million barrels of crude oil a day, about half of Nigeria’s total daily production. And oil exports made up more than 95% of the country’s foreign earnings. As a result, Shell wielded tremendous influence over the country’s military government.

So when MOSOP’s peaceful protests were met by violence of the military government, including numerous beatings, rapes, and killings, there were claims that Shell, which had urged the president to solve “the problem of the Ogonis and Ken Saro-Wiwa,” was complicit. As Amnesty International described in its report on Shell’s role: “Even after the men were jailed, suffering from mistreatment and facing an unfair trial and the likelihood of execution, Shell continued to discuss ways to deal with the ‘Ogoni problem’ with the government rather than expressing concern over the fate of the prisoners.”

The reputational issues for Shell have lingered for three decades. In 2009, on the eve of a trial in New York, the company agreed to pay more than $15 million to settle a legal action in which it was accused of having collaborated in the execution of the Ogoni nine — one of the largest payouts agreed by a company accused of human rights violations. And in 2017, Amnesty was still calling on Nigeria, the UK and the Netherlands to launch an investigation into Shell’s role in the killings.

On the environmental front, meanwhile, just three years ago France 24 reported: “The Ogoniland area of southern Nigeria is one of the most polluted places on Earth. The crops are burnt to a cinder, ash and tar smother the land and the wells are polluted with oil, making the water totally undrinkable. Entire communities have suffered as their way of life has been destroyed by the oil industry.” And just last year, the High Court in London ruled that Nigerian villagers can bring human rights claims against the company Shell over chronic pollution in the region.

In 2001, I spoke with Gavin Grant, then chairman of Burson-Marsteller, who talked about how the Saro-Wiwa case caused companies to rethink corporate social responsibility in emerging markets. “I think Shell took the view that internal politics in Nigeria had nothing to do with them,” he said. “I don’t think it was a cynical view. I think it was a very genuinely held view that they should stay out of issues that did not directly impact their business.”

Shell had been forced to recognize that such a view was untenable. In 2009, I spoke with Bjorn Edlund, at the time head of the company’s external relations function, who conceded: “Our approach in Nigeria, making determined representations for clemency ‘behind closed doors,’ while not commenting publicly, was seen as the silence of complicity while human rights were being trampled.” As a result, he said, “structured, proactive stakeholder engagement became the job of senior business people in Shell.”

The Now Lesson

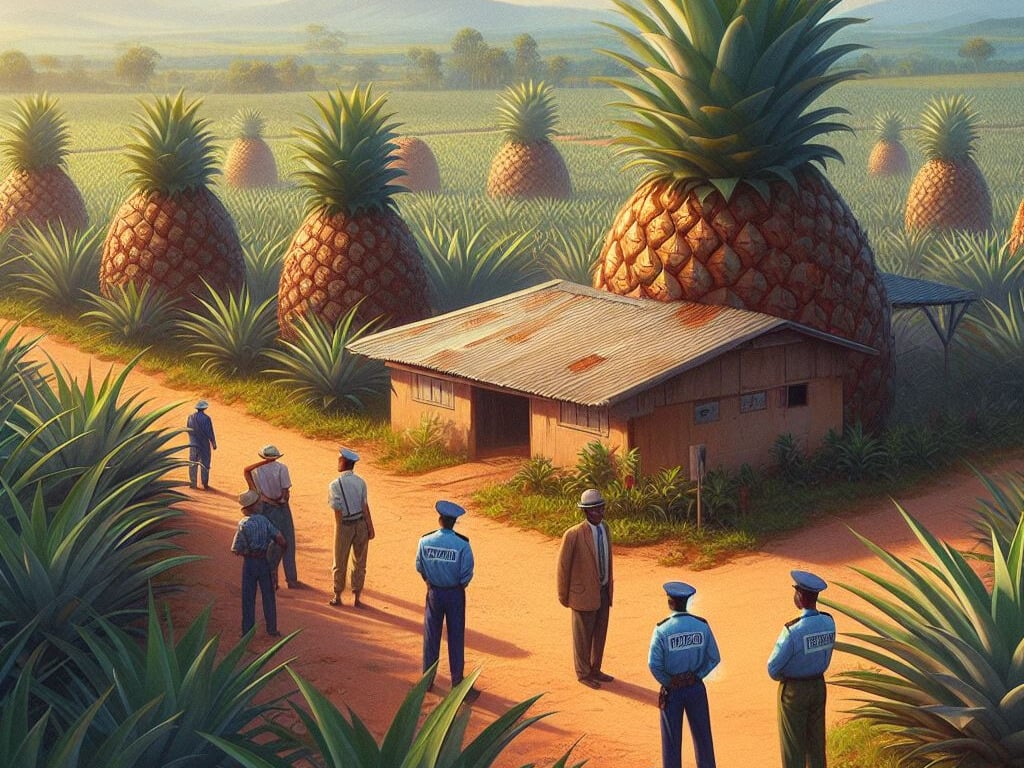

In December, a human rights group and community activists filed a lawsuit against the giant food company Del Monte after assaults and killings at a pineapple plantation near Nairobi, Kenya.

The company, which employs 6,000 people in Kenya, has been the target of attacks by the local community, which claim that Del Monte’s plantation is located on ancestral lands. The company has faced accusations of violence in the past, but the most recent involved the suspicious deaths of four men accused of trying to steal pineapples from the Del Monte plantation.

The lawsuit alleged that tensions between the company and the community had led “to conflicts with the security personnel deployed by Del Monte, who assault, beat, torture, maim, rape and/or kill the trespassers.”

A subsequent story in The Africa Report quoted a former Del Monte security guard who claimed: “The instructions [from the company] were very clear: when you see a thief, you chase him until you arrest him and you beat him up brutally.” The same report quoted a man who admitted that he had been attempting to steal pineapples and saw four other men attacked by guards: “After being beaten, it appears the guards thought they were dead. To hide the evidence, they threw their bodies into the river,” he said.

Del Monte’s response, at a hearing in Thika this week, was that it should not be held liable because it is domiciled in the Cayman Islands “outside the jurisdiction of this honorable court.”

Without commenting on the legal merits of that argument, I can say that from a public relations perspective, it’s the kind of response that can guarantee three decades of misery. The court of public opinion is likely to see it as an attempt to weasel out of legal responsibility — and a pretty clear admission of moral culpability.

I would suggest five lessons that Del Monte — and other companies doing business in developing markets — should learn from previous incidents:

1. Cultural relativism is no defense. There was, perhaps, a time when the expectations of corporate behavior in the developing world were different than they were in developing markets, which meant that companies could simply claim to be complying with local legal standards and expect a free ride. But we are now in a global news environment, and many consumers in America and Europe don’t want to do business with companies that still believe they can treat more vulnerable populations badly.

2. You can’t hide behind corporate structures. Shell spent years patiently explaining to people that Shell Petroleum Development Company was a subsidiary for which the parent company could not be responsible. Union Carbide did the same after Bhopal. Del Monte appears to be going down the same path. Whatever the merits of these arguments in a court of law, they have no feasible chance of success as a PR strategy. Your name is on the company. You’re responsible. End of story.

3. Rogue actors — or rogue governments — won’t protect you. Shell did not hang Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Nigerian government did. Perhaps it did so at the behest of the company; perhaps it was just trying to be “helpful.” The Del Monte security guards might have been following company orders or they might have been over-zealous employees. From a reputational standpoint, it doesn’t much matter: it was done for your benefit, and unless you are seen to be taking every possible step to discourage it and to punish those responsible, you will be blamed.

4. Other companies care about supply chains. More than ever before, consumer-facing businesses take an interest in the behavior of their suppliers. The British supermarket chain Tesco has already suspended purchases of Del Monte products as it worries that its reputation might suffer by association. Other companies have demanded an independent investigation. In this environment, companies involved in human rights abuses feel the business impact immediately.

5. Allowed to fester, the damage can last for decades. If you don’t take responsibility now, you will be facing questions about your role that persist for years. Every time a new legal action is filed, your name will be in the headlines again. Every time another company gets embroiled in a human rights controversy, your company will be held up as the object lesson.

.jpg)