NewsWhip 01 Jun 2020 // 7:06PM GMT

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the center of the media universe for more than two months now, with engagement to the topic comfortably topping that of all other news stories combined.

Unfortunately, some of that engagement has been on stories and narratives with poor foundation in facts. How severe are the hoaxes and misinformation around COVID-19? And what should we expect next from the “infodemic”?

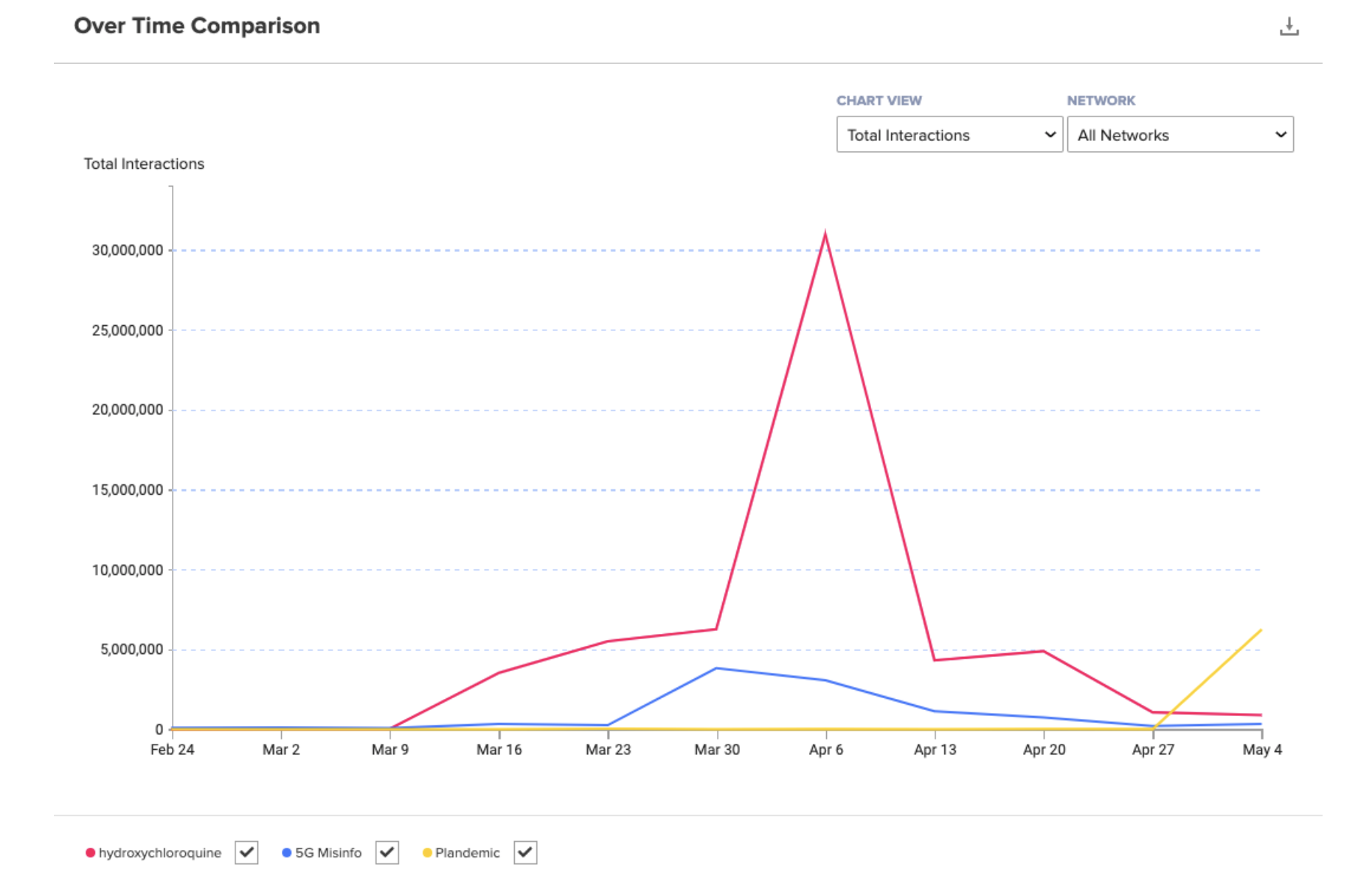

Today I’ll explore misinformation on three major topics: hydroxychloroquine, 5G, and the ‘Plandemic’ documentary - and see what common patterns link them. NewsWhip gathers precise data on media engagement and has four years of experience supporting anti-misinformation work in the Americas, Europe and Asia - so we have good foundational data for the analysis.

Hydroxychloroquine and President Trump

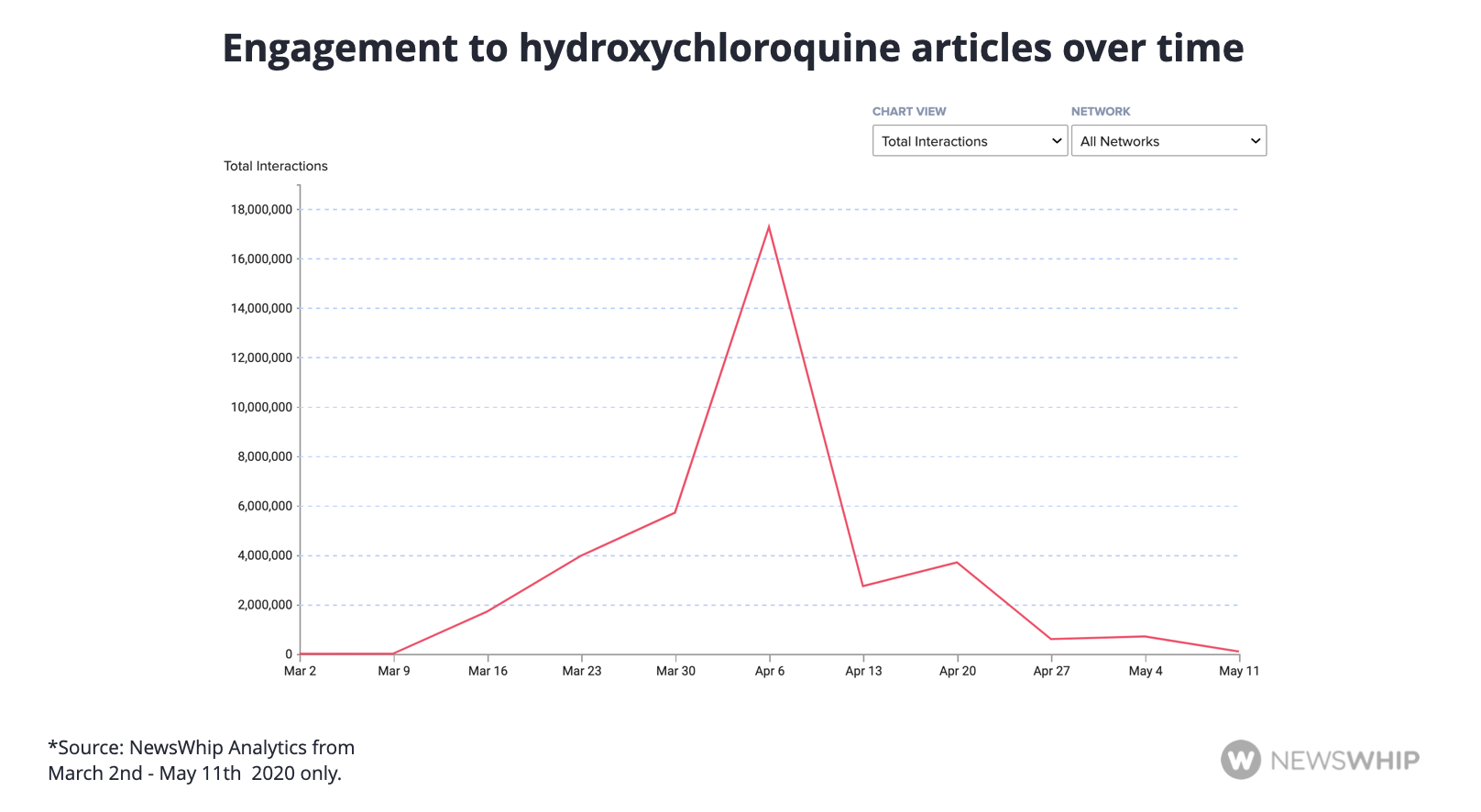

Hydroxychloroquine was one of the first misinformation flashpoints in the coronavirus era, and was by far the biggest controversy of the three we explore today - attracting up to 17 million engagements per day at its peak.

This began around the beginning of March, when a Dr Zelenko claimed to have treated 100 percent of his Covid-19 patients successfully with hydroxychloroquine. This was picked up by fringe sites and also by conservative media, where it received heavy traction. Some experts suggested the evidence was anecdotal, but the cure attracted the attention of President Trump.

Hydroxychloroquine treatment is not precisely misinformation - in fact, it has been widely used as such, though is now disavowed by the WHO. However, it shaded into misinformation when political leaders promoted it as a complete cure-all to COVID-19. Multiple trials show it is not - and it can instead harm outcomes for some patients through heart incidents.

Even as evidence emerged about the potential dangers of the drug, the White House promoted it at press briefings, despite an internal fight going at the White House. Fox news promoted the drug extensively, and approval or disapproval of it became a tribal badge, with skeptics of the severity of COVID-19, generally conservatives, promoting the “simple” cure, and those more concerned with the disease criticizing its efficacy.

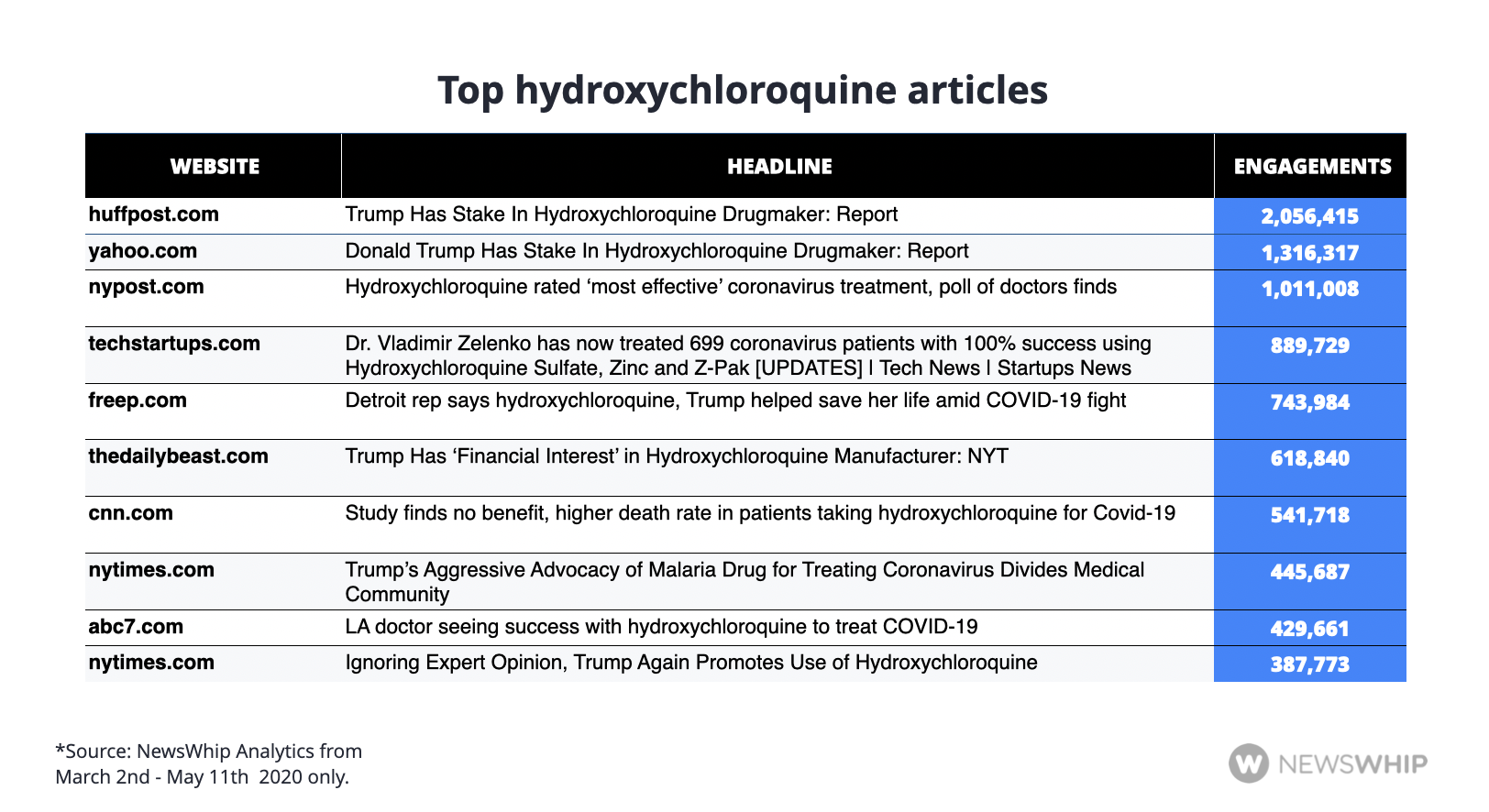

What have people been sharing on the topic? The most engaged media about hydroxychloroquine are actually stories suggesting that President Trump has a stake in a producer of the generic version of the drug.

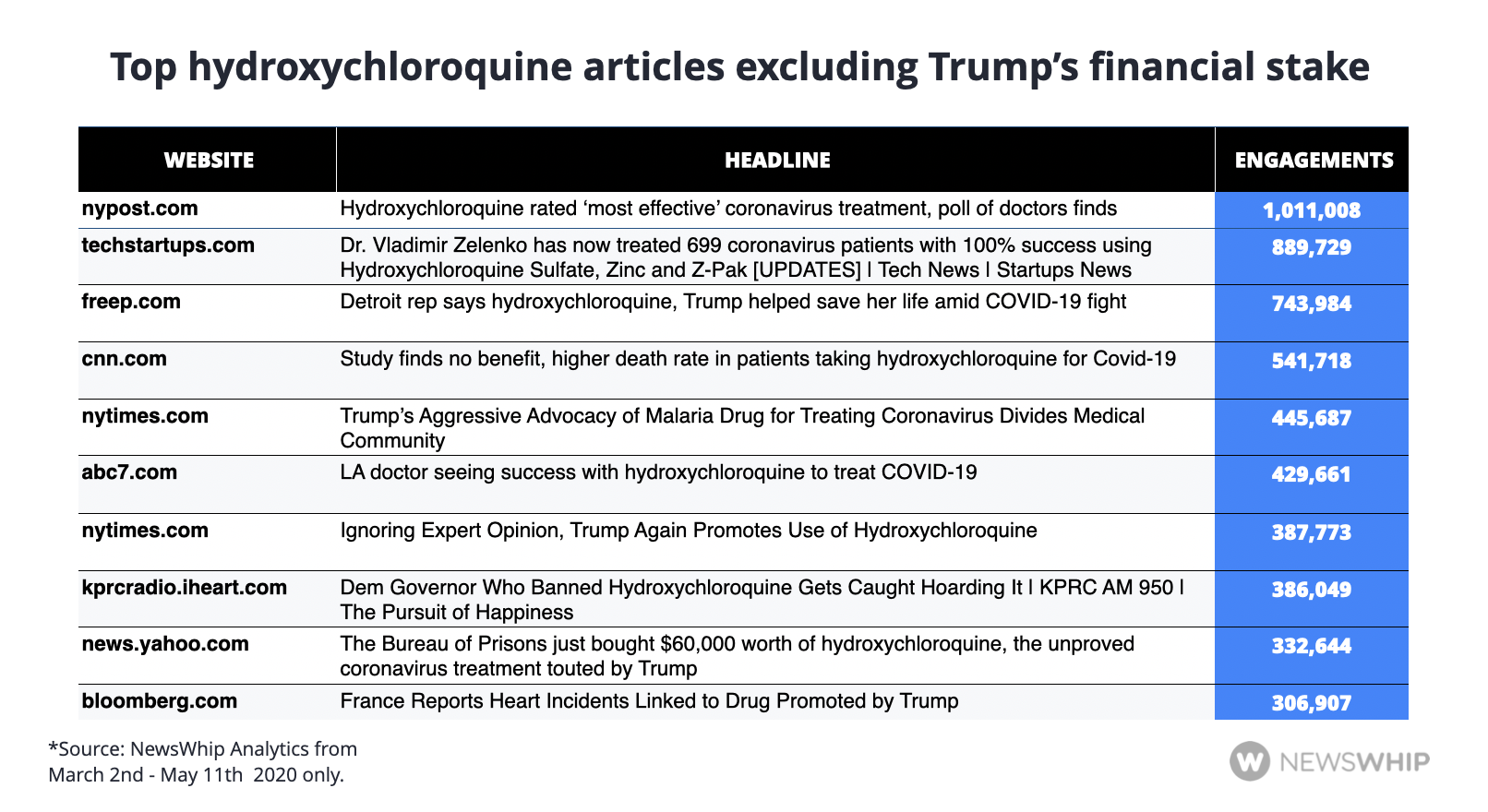

Removing the articles about this financial stake, we find the most engaged stories promote heavily its effectiveness (poll of doctors finding it “most effective”) or not (treatment “divides” the medical community). This appears to be members of each political tribe promoting their view on the drug. Some right wing publishers (like the New York Post) saw engagement on stories promoting it, and mainstream and lift wing media (CNN) saw engagement on stories cautioning against it. This reflects individuals sharing stories that promote or detract from the drug, depending on their political leaning.

Another highly engaged narrative emerged in the last two weeks, when Donald Trump claimed he was taking the drug. This story drove around 1.1 million engagements for NBC News.

Interestingly, the drug has received significantly more engagements than remdesivir, an antiviral drug that has shown more success combatting the virus in early trials. Articles about hydroxychloroquine drove 36 million engagements, compared to around 4 million for remdesivir to date.

Perhaps this is a good thing for remdesivir, which has not been politicised in the same way as hydroxychloroquine - it’s neither ‘red’ nor ‘blue’. At least not yet.

5G and Covid-19

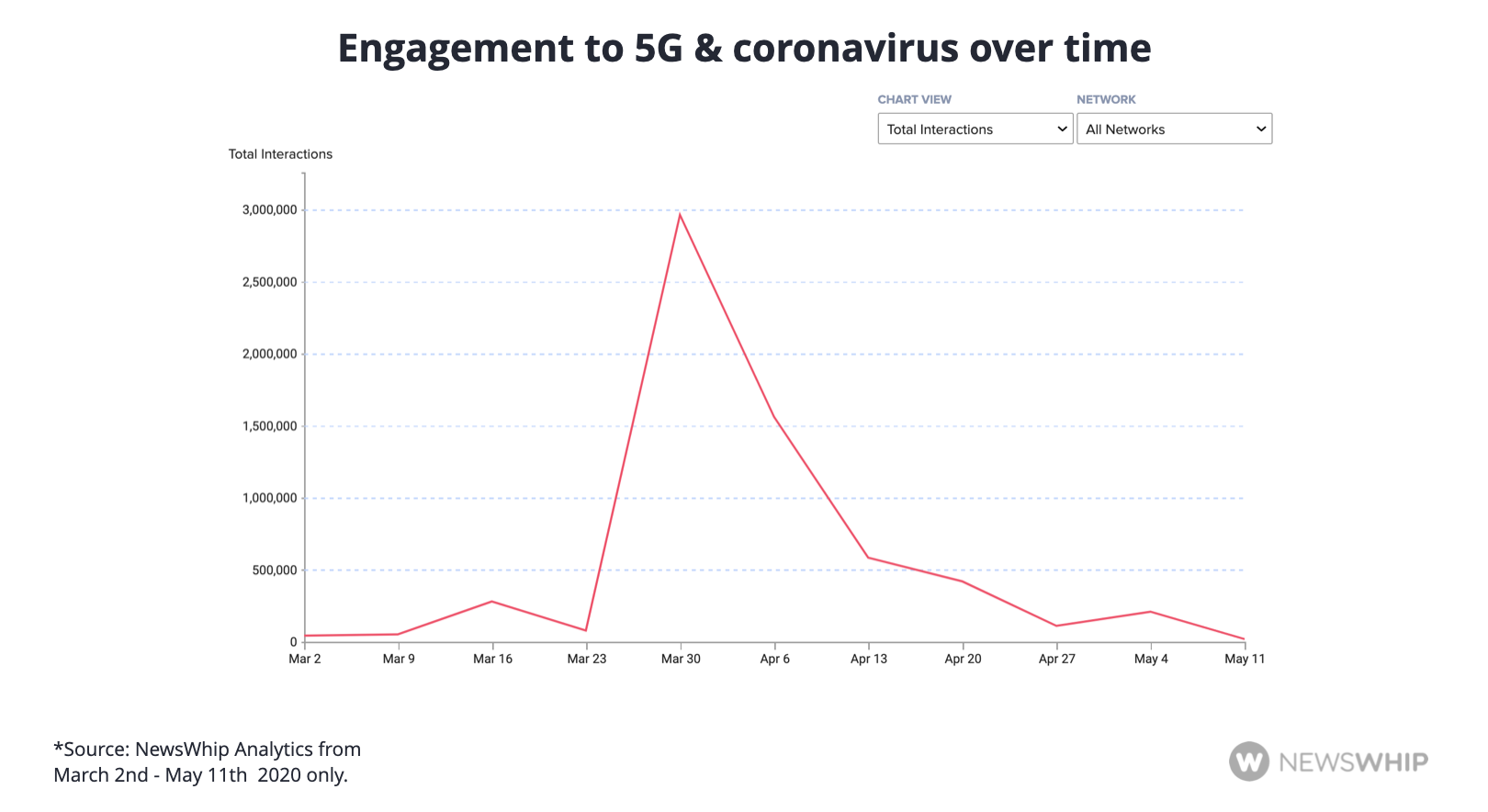

5G and coronavirus was another theme that has seen a good deal of attention in the misinformation sphere in the past two months, with misinformation suggesting a link between the 5G and the virus.

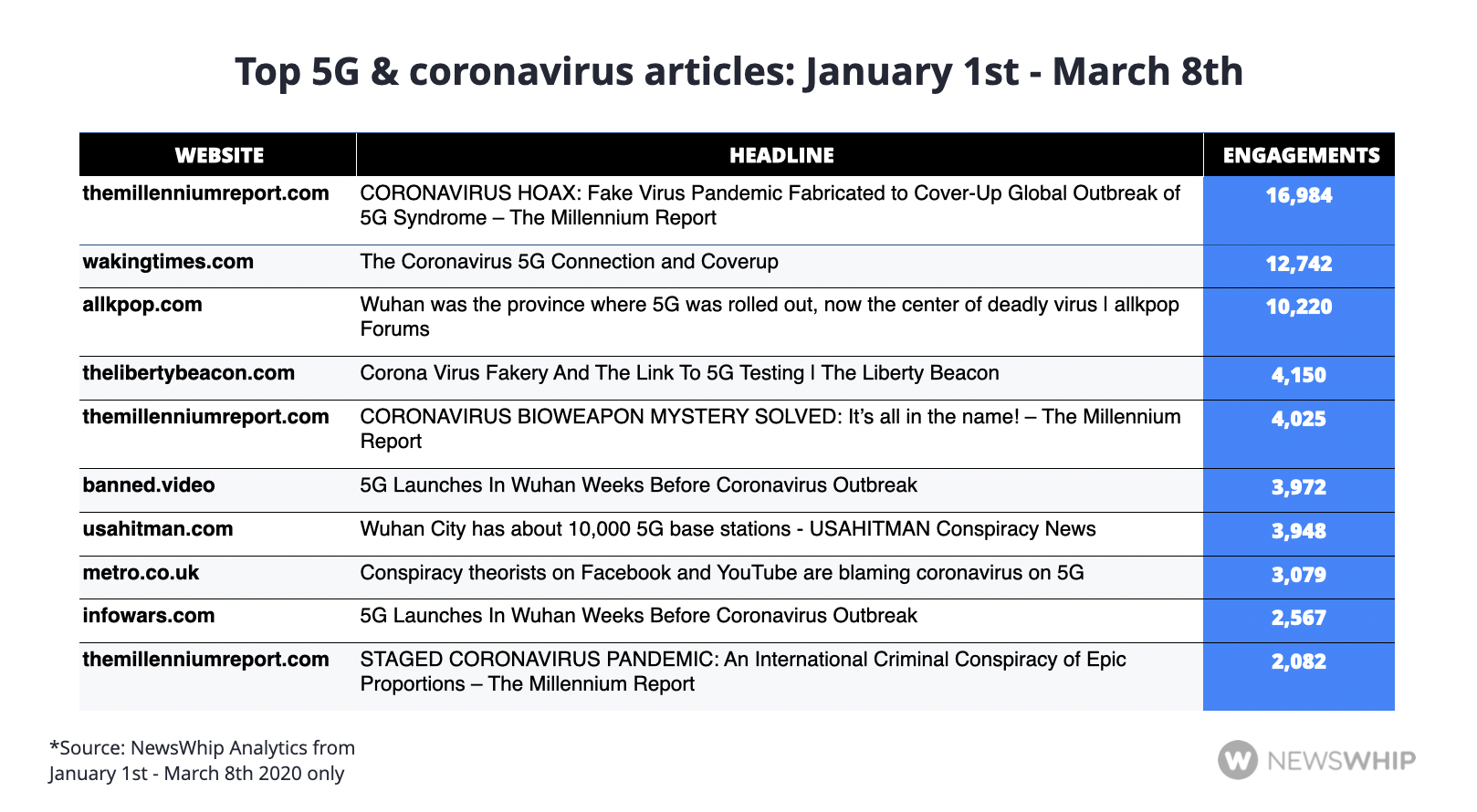

The beginning of the year saw some of the top articles about 5G and coronavirus being active misinformation. The chart below shows the top articles through March 8th of this year.

Various sites peddled conspiracy theories - though the early engagements number in thousands, not millions. The only article within the top ten that attempted to debunk the conspiracy theories during this time came from the Metro.

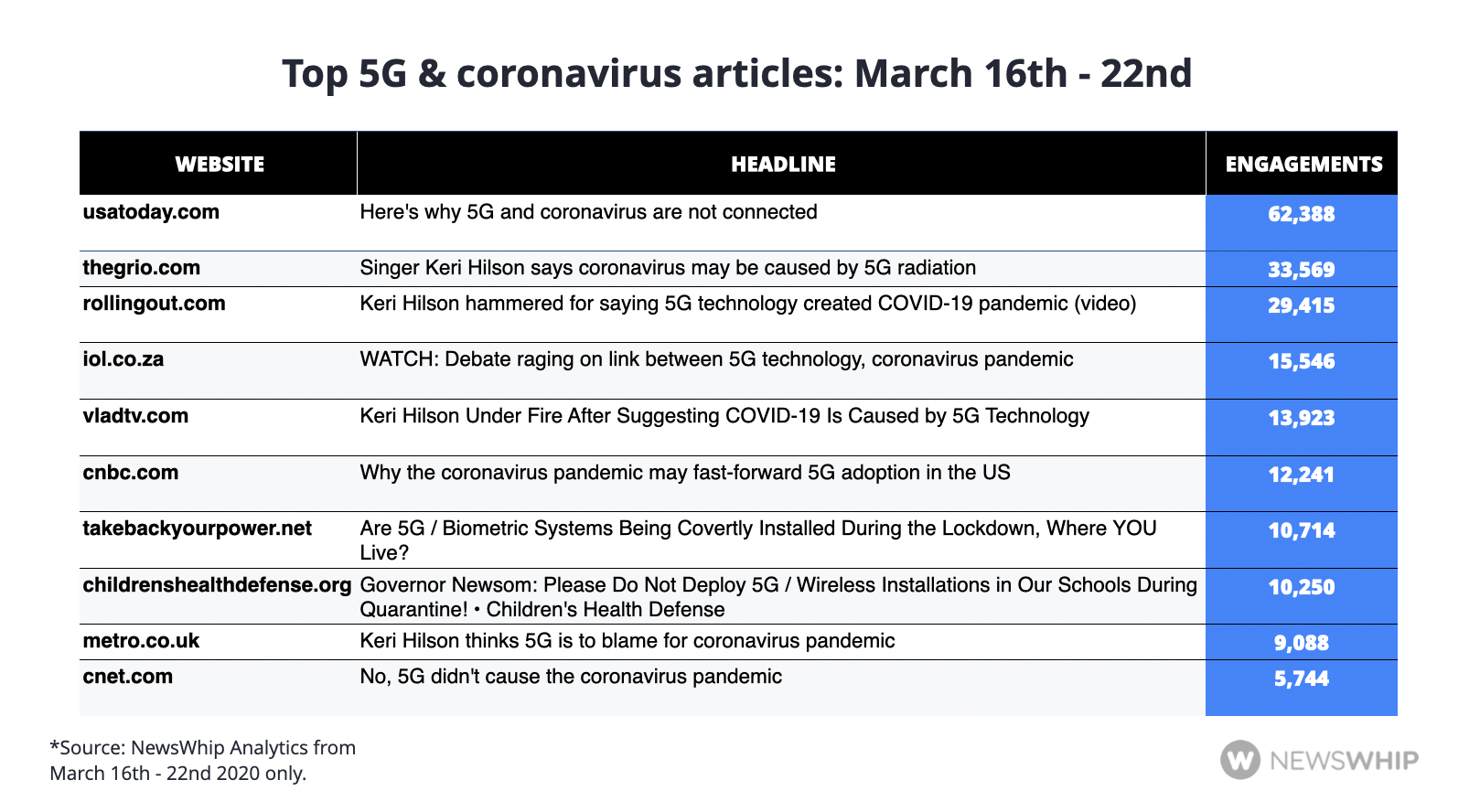

Attention began to pick up March 16th, as theories spread online and were signal boosted by some celebrities. This is when media organizations began to debunk the theory more aggressively too.

Keri Hilson was criticized in many publications for wondering aloud whether there was any link between the virus and 5G, with four of the top ten articles of the week about the singer’s comments.

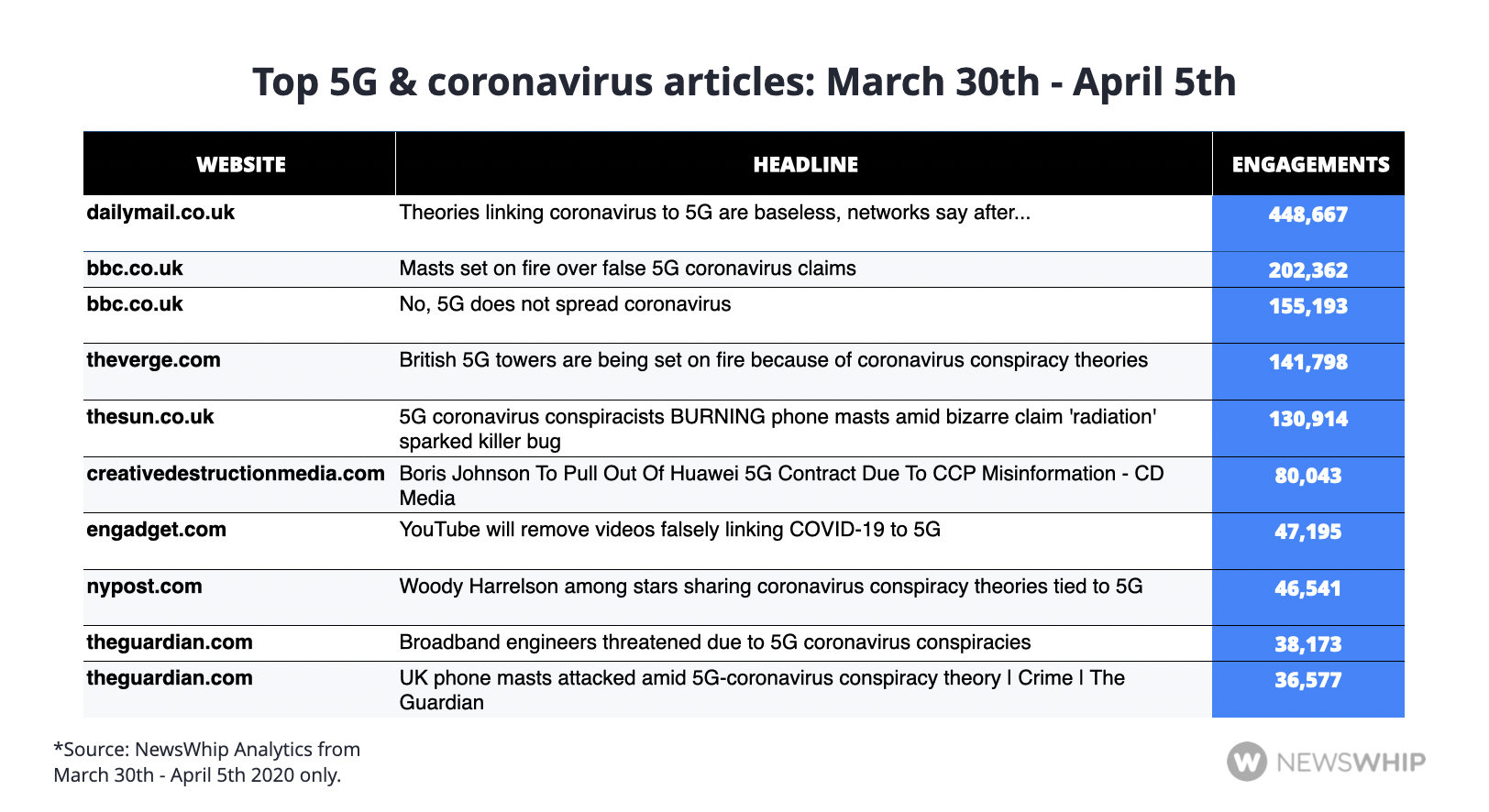

Engagement started peaking on the week of March 30th when big publishers wrote debunking pieces, and these were shared and engaged with by audiences on a mass scale. Perhaps people on Facebook were getting exasperated by seeing their friends sharing misinformation - and news pieces like the BBC’s “No, 5G does not spread coronavirus” were a welcome way to respond.

The top article came from the Daily Mail, while the BBC, The Verge, The Sun, and The Guardian were all involved in reporting and debunking the conspiracies. A viral rumor that Boris Johnson was set to pull out of a 5G deal with Huawei was the fifth most engaged article of that week, but had no basis in fact.

Given the low levels of Facebook engagement on the stories promoting the theories themselves, it seems that Facebook’s anti-misinformation interventions on its main platform may have been effective. Given the reach of the conspiracy theories, they must have other vectors of spread - anecdotes from my friends suggest WhatsApp has been a hotbed of misinformation.

'The Plandemic'

Another of the most viral pieces of misinformation to happen so far is 'Plandemic documentary', which briefly went viral on a number of social platforms. The Plandemic is a well produced but nonsensical video purporting to challenge established narratives about the coronavirus. It features a well-known anti-vaxxer named Judy Mikovits making various claims about the virus.

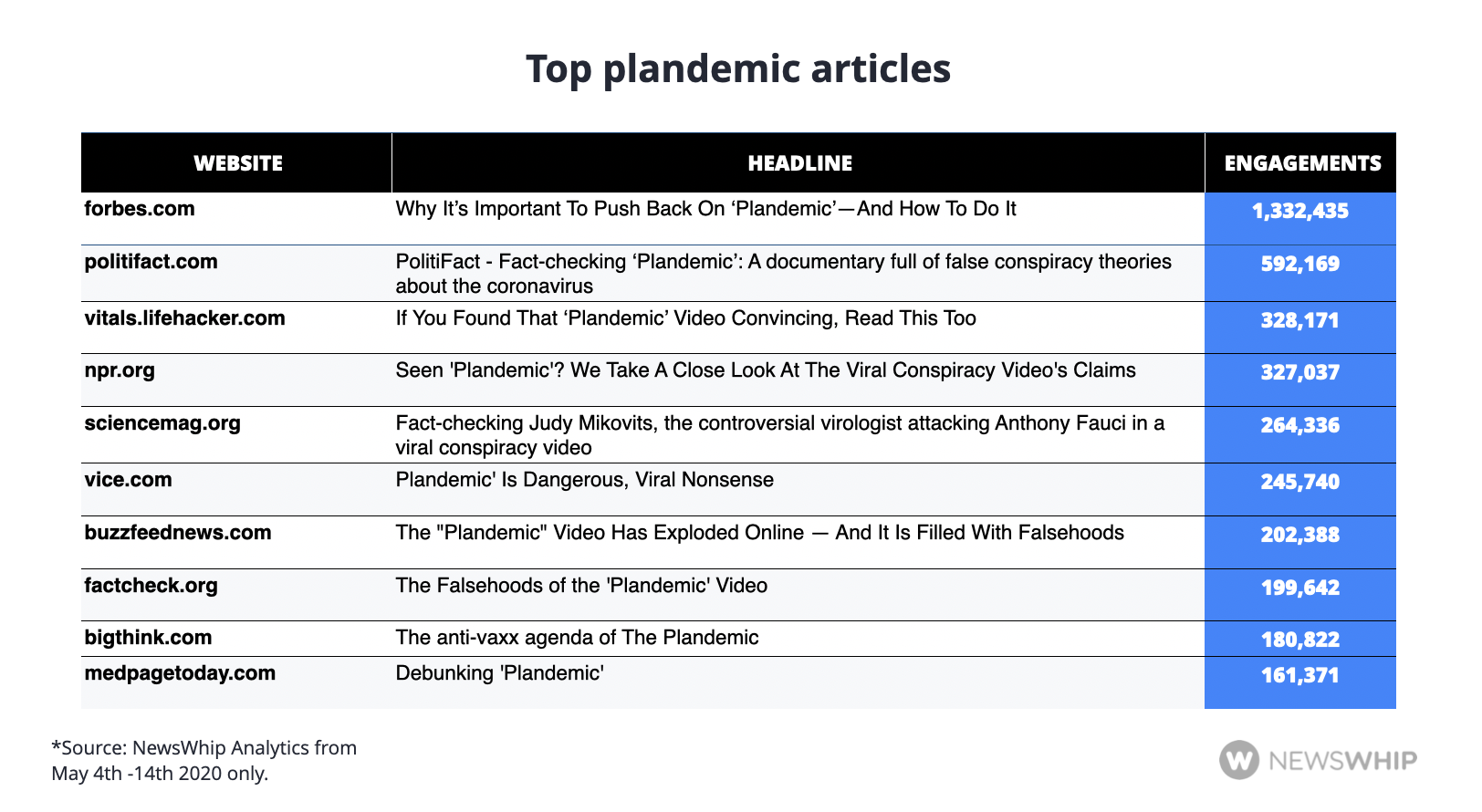

The information was deemed so misleading that all of the major content platforms, including Facebook, Vimeo, and YouTube, all took the decision to remove it from their sites. It has been debunked by various publishers, and these debunkings have received high engagement.

The Big Think's piece on the matter focused on the anti-vaxx origins of the participants in the documentary, receiving 150k engagements, and BuzzFeed’s piece on the video received 56k engagements.

BuzzFeed focused on what makes the piece believable at first glance, with its high production value and authoritative sounding figures, before again exposing the long-debunked claims of the video and anti-vaxx past of the main subject of the documentary.

The top story about the plandemic actually came from Forbes, and offered advice as to how to approach people you knew that had shared the video.

All of the top web articles either debunked or offered the counter narrative to the video. This was a video designed to spread on social natively, but it is a positive note that all of the top web articles came from big publishers fact-checking and challenging the original.

Misinformation Tribes

All of the misinformation narratives have a common thread: they start in the fertile beds of existing communities predisposed to believing them. They eventually spring from this ground into the mainstream - where the force of rebuttal, fact checking and full-on censorship by the major platforms tends to stop them from spreading further into common consciousness.

However, they do appear to live on in these smaller groups. For example, Plandemic seems to be popular with the anti-vax community. The 5G coronavirus appears to be popular with other, harder to define, marginal groups. The idea of Hydroxychloroquine as a cure-all came from the hopes and allegiances of the American right.

If you’re advising a brand caught up in the slipstream of a major misinformation narrative - remember that it’s extremely hard to convince the true believers of the other side.

Research shows that while people will update their beliefs about facts about the natural world when presented with counterevidence, we are extremely resistant to doing so when a fact contradicts a belief about our political or moral values. In other words, if your “facts” contradict something I hold dear, I’ll find a million reasons not to believe you. “Even a careful factual response to a controversy might receive zero pickup with a group strongly motivated to distrust anything that counters their beliefs.“

Accordingly, at least early on, it might be worth allowing a misinformation narrative popular with a small group to burn itself out rather than give it fuel through a denial. Many of our users do so by monitoring popular Facebook pages and media outlets of the “tribes” who obsess about their industry.

Monitor vigilantly. If a false narrative does break out into a larger tribe, or the mainstream, the advice of fact checking organisations (such as First Draft) is to speak up - sometimes the only way to drown out misinformation is a flood of facts.

.jpg)

.png)